In the century after John Barbour’s Brus (1375), there is more and more evidence of literature written in Scots. Notable examples include an extended love poem, The Kingis Quair (‘The King’s Book’) attributed to James I of Scotland. The poem appears to be an idealised account of the young king’s capture and imprisonment by the English, between 1406 and 1424. While imprisoned, James met Joan Beaufort, the daughter of the Earl of Somerset, and pressure from her family ultimately secured his release. James and Joan were married, and she acted as Queen Regent of Scotland on his untimely death.

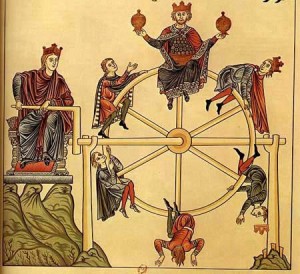

Although the lovers are not directly named, and although the poem is allegorical, complete with a dream vision of fortune’s wheel, The Kingis Quair follows the general story of James I and Joan Beaufort, in that it tells of a young man who falls in love with a beautiful woman, seen from his prison window. The Kingis Quair is one of the earliest surviving Scottish poems to be influenced by The Consolation of Philosophy, a work written the late Roman philosopher, Boethius (480-524/5).

The Consolation of Philosophy also has a prison theme – Boethius reflects on the variable nature of fate, which had brought him from the position of senator to condemned convict. Boethius’ moral – his consolation – was for individuals to resign themselves to providence, and to accept the way in which fortune’s wheel either raises or lowers them. The variability of fortune was to prove a powerful and recurring theme in the literature of the turbulent mediaeval period.

The later fifteenth century also saw the composition of Blind Hary’s Wallace, or more properly The Actes and Deidis of the Illustre and Vallyeant Campioun Schir William Wallace (1477). This bloodthirsty epic is often seen as a later companion piece to Barbour’s Brus (not least because the earliest manuscripts of both poems are in the hand of the same scribe, John Ramsay); it has been adapted and updated several times over the centuries and can be considered the main source material for the screenplay for the Hollywood film, Braveheart (1995), which was scripted by Randall Wallace.

Other types of writing in Scots begin to appear in this century too: Sir Gilbert Hay was a poet and a translator of treatises on military topics, the rules of knighthood, and the characteristics of good government. And – significantly – the Acts of the Parliament of Scotland and the Burgh Laws were now being recorded not in Latin, but in what we now would call Scots. The writers themselves still generally called their language ‘Inglis,’ when they wished to distinguish it from ‘Erse’ (‘Irish’, that is, Gaelic). Towards the end of the 15th century there arose amongst some, at least, that what was increasingly becoming the national written language of Scotland was different from that of the neighbouring kingdom to the south, and the term ‘Scottis’ begins to appear.

The two poets or ‘makars’, to use the mediaeval term, whose work forms the focus of this chapter, belong to the end of the fifteenth century and the early years of the sixteenth. They are considered to be amongst the finest European poets of their period, and their poetry serves to point up the range and contrasts in Scottish literature of the time. The main, interconnected centres of literacy were the court, the church and the university. Many courtiers could read and write, and the court also employed clerics in both religious and administrative roles.

At court there was also an appetite for entertainment, and those who were literate and gifted in poetry and song hoped to find an appreciative audience, and generous patrons. Even beyond the strict confines of the court, noble families might commission a writer to produce a fine translation or an original text – or they might patronise a writer who dedicated work to them. William Dunbar (c.1459-c.1525), who was probably a graduate of the University of St Andrews, served as a cleric at the court of James IV, and the bulk of his poetry is connected with either religion or court life. Indeed many of his poems have an ‘occasional’ quality, in that their topics are suggested by particular court events, such as the marriage of James IV to Margaret Tudor, daughter of Henry VIII, in 1503, or by the failure of a fraudulent Italian alchemist to fly from Stirling Castle battlements, all the way to Paris, in 1507.

Most of all, however, it is the stylistic range of Dunbar’s writing that still has the power to amaze. Dunbar was able to turn his hand from poems of religious praise, echoing and extending the very early Latin and Gaelic traditions that we mentioned in Chapter 1, to ribald sexual satire, as in his Tretis of the Tua Mariit Wemen and the Wedo (‘Treatise of the Two Married Women and the Widow’). His ‘Ane Ballat of Our Lady’ show how the Latin tradition of praising the Virgin Mary has seeped into the very vocabulary of written Scots:

Hale, sterne superne, hale in eterne,

In Godis sicht to schyne,

Lucerne in derne for to discerne

Be glory and grace devyne,

Hodiern, modern, sempitern,

Angelicall regyne,

Our tern inferne for to dispern

Help, rialest rosyne.

Ave Maria gracia plena.

Haile, fresche floure femynyne,

Yerne us guberne, virgin matern,

Of reuth baith rute and ryne.

The poem represents a mediaeval aesthetic that was highly valued at the time but is perhaps more difficult to grasp today. The poem’s worth would have been self-evident to poets schooled in classical literature and Latin as part of a university curriculum that placed an emphasis on elaborate rhetoric. The words in italics can be considered ‘aureate’ vocabulary – they help to make the verse ‘golden’ by helping it transcend everyday speech.

There are two sides to aureation – the most obvious is a preference for using new-fangled terms derived from Latin. If you look some of these expressions up in the online Dictionary of the Scots Language, you will see that Dunbar is often the first (and sometimes the only) person to have used the term. Often native words from Old English or Old Norse were available synonyms for the latinate expressions; for example, he might more easily have written queen for ‘regyne’ or today for ‘hodiern’. But then the poem would not have sounded so grand – and this is a poem that largely exists to sound grand.

Not all Latin loan-words had native synonyms – some terms, like vice, entered the language to describe concepts that were not adequately expressed in English, Norse or Scots. These tend to be technical terms, often religious or legal, and in the words of one scholar, Bengt Ellenberger, they increase the semantic breadth of the language, unlike the purely decorous words, which increase its semantic depth. Aureate latinisms, then, are a clear marker of high-style poetry of celebration, religious or secular.

But some of the words italicised in the poem are native Old English and Old Norse terms that survived into Scots. Sterne (‘star’) is an aureate word from Old Norse – it owes its ‘aureate’ categorisation not to its etymology but to its meaning: it falls into one of the positive semantic fields associated with the high style, celebratory rhetoric, for example, holiness, purity and light. Together with the decorous latinisms, native terms expressing these positive concepts make the verse ‘golden’.

As well as vocabulary, there are other markers of aureation. Since Chaucer and Lydgate were notable predecessors in writing elaborate, vernacular (i.e. non-Latin) poetry, the Scottish makars nodded to their southern counterparts by using occasional anglicisms. Sometimes they went too far. Knowing that the English equivalent of fra is ‘fro’ or ‘from’, Dunbar seems to have assumed that the bird, the lark, would become ‘lork’ in English. If he thought that, he was wrong, but that is the form used in his poem to celebrate the marriage of James IV and Margaret Tudor, ‘The Thrissill and the Rois’, which begins:

Quhen Merche wes with variand windis past,

And Appryll had with hir silver schouris

Tane leif at Nature with ane orient blast,

And lusty May, that muddir is of flouris,

Had maid the birdis to begyn thair houris

Amang the tendir odouris reid and quhyt,

Quhois armony to heir it wes delyt:

In bed at morrow, sleiping as I lay,

Me thocht Aurora with hir cristall ene

In at the window lukit by the day

And halsit me, with visage paill and grene;

On quhois hand a lork sang fro the splene,

“Awalk, luvaris, out of your slomering!

Se how the lusty morow dois up spring.”

Another indication of the high style is a complex rhyme scheme: aureate poems wore their difficulty as a badge of pride. And, of course, the decorous vocabulary and elaborate rhymes were fitted to appropriate topics, such as the celebration of the virgin or the marriage of the king.

There is some debate about whether complex grammatical structures are indicators of the high style. While they do appear in some poems, in Dunbar a constant feature of all styles of his poetry is grammatical parallelism: there is nothing he likes better than to pile up a list of epithets or repeated phrase types. This happens a little later in ‘The Thrissill and the Rois’ for example, when James IV is introduced, in the heraldic form of a lion rampant:

This awfull beist full terrible wes of cheir,

Persing of luke and stout of countenance,

Rycht strong of corpis, of fassoun fair but feir,

Lusty of schaip, lycht of deliverance,

Reid of his cullour as is the ruby glance.

On feild of gold he stude full mychtely,

With flour delycis sirculit lustely.

If you unpick the grammar of this verse, and substitute the adjective phrases (like ‘terrible…of cheir’) with letters (A…of B) then it is clearly built on repeated structures, with occasional variations:

This awfull beist A wes of B,

C of D and E of F,

Rycht G of H; of I, J but [= without] K,

L of M, N of O,

P of his Q as is R.

On feild of gold he stude full mychtely,

With flour delycis sirculit lustely.

While intricate, this level of complexity is not unique to high-style celebrations, as we shall see. However, in most respects, the ‘low style’ is the linguistic mirror image of the aureate high style. The low style describes the literary language that is appropriate to satire, comedy and that peculiar form of poetic contest called ‘flyting’, when participants insult each other by using flamboyant obscenities that increase in intensity. In such poems, rather than latinisms, northernisms and words of obscure etymology are favoured. If Latin loan-words are evident, they tend to be technical terms or words with negative meanings or associations. There is little evidence of Anglicisation. Rhyme schemes are simpler, and while grammatical constructions might show condensed or elided features, similar to speech, there is often still a high degree of parallelism. Low-style qualities are evident in Dunbar’s ‘The Dance of the Sevin Deidly Sins’, a poem based, again, on a religious theme, but which treats the monstrous nature of the cardinal sins with a grotesque, comic glee. Dunbar claims to have seen the dance in a dream – dream visions were again common subjects of mediaeval poems. This is the entry into the dance of ‘Lechery’:

Than Lichery, that lathly cors,

Come berand lyk a bagit hors,

And Lythenes did him leid.

Thair wes with him ane ugly sort

And mony stynkand fowll tramort

That had in syn bene deid.

Quhen thay wer entrit in the dance,

Thay wer full strenge of countenance

Lyk turkas birnand reid.

All led thay uthir by the tersis.

Suppois thay fycket with thair ersis,

It mycht be na remeid.

Then Lechery, that horrible creature

Came bearing himself like a pregnant horse

And Wantonness did lead him

There was with him an ugly assortment

And many stinking, foul corpses

That had been dead a long time.

When they were entered in the dance

They were completely strange in appearance

Burning red as a blacksmith’s tongs

They all led each other by the genitals.

Even if they fidgeted with their arses

It could not be helped.

Here, and elsewhere in the poem, there are many northernisms – like fycket, from the verb fyk, which seems to be related to Old Norse fíkjast and Middle Swedish fikja, ‘to be eager or restless’. Elsewhere in the poem, we find other words that are part of the Viking legacy to the Scots tongue: graith ‘prepare’, rumpillis ‘tails’, ockeraris ‘usurers’ and midding ‘midden, or rubbish heap’. These and their fellow northernisms give this poem a very different lexical texture from the hymn to Mary.

The grammar of ‘The Dance of the Sevin Deidly Sins’ is also, perhaps, more apt to omit features than a high-style poem – it has the clipped nature of speech perhaps. This is evident in the first two lines of the verse quoted above:

Than Lichery, that lathly cors

[Come] berand [himself] lyk a bagit hors

In some manuscript versions of the poem, the verb ‘come’ is omitted, in others it is included – giving modern editors the dilemma of whether or not to make the grammar rougher or smoother – more or less imitative of speech, perhaps. Certainly the expected reflexive pronoun after ‘berand’ is absent in all versions. But elsewhere the grammar is relatively complex, as in this verse, which observes that musicians were banned from this dance, except one who, who was allowed to enter because he had committed murder, and so he was entitled to his inheritance (in legal jargon, he was due his ‘brief of right’).

Na menstrallis playit to thame but dowt

For glemen they were halden owt

Be day and eik by nicht –

Except a menstrall that slew a man;

Swa till his heritage he wan

And enterit be breif of richt.

For players were kept out

By day and also by night –

Except a minstrel who killed a man;

So he earned his inheritance

And entered by ‘brief of right’

There is little evidence of southern forms in this poem – Scottish swa, for example, is preferred to English so – and the rhyme scheme is simpler than in most high style poems. The rhyme is aabccb, on the whole, with the couplets being tetrameter and the b-rhymes trimeter – allowing a kind of punch-line of acerbic observation after little units of description, as in the following passage that describes the followers of Gluttony:

Full mony a waistless wallydrag

With wamys unweildable did furth wag

In creische they did incres:

Drynk! ay thay cryit, with mony a gaip –

The feyndis gaif thame hait leid to laip –

Their lovery wes na les.

Many a slob lacking a waist

With unweildable stomachs wagged forth

In fat they did increase

Drink! They always cried, with many a gape –

The demons gave them hot lead to lap –

Their rations were no less.

The poem begins by quoting a date for the dream vision – 15th February. Scholars are unsure about the significance of the date: in some years it might have coincided with the beginning of Lent, and so we might imagine the poem being performed to a court audience at the start of a period of abstinence, and the renunciation of the vices being described in the poem. If not, then the date might just be a conventional reference to the date of a supposed dream, a way of adding some credibility to a fantastic vision. Again, we can imagine the poet performing the poem aloud for the enjoyment of a court audience, which would, no doubt, have revelled in its disgusting imagery – and appreciated the energy that Dunbar brought to the low-style composition.

A final group of poems by Dunbar is more difficult to describe, stylistically, except to say that the verses are neither high nor low style: they avoid aureate latinisms or vivid northernisms, and the excesses that mark both the high and low styles. They are therefore dubbed ‘plain style’ poems and though they are difficult to categorise, they are substantial in number, amounting to about a quarter of Dunbar’s surviving work. They tend to be more ‘personal’ in nature, and include meditations on illness and on mortality – and they also include a series of poems addressed to the king, asking for favours. These ‘petitionary poems’ give another insight into the function of literature in the mediaeval Scottish court: it was one means by which the poet might receive privileges, though the relationship between poet and patron was, understandably a tricky one to negotiate. Dunbar’s petitionary poems construct his relationship with the king as an occasionally fraught one, especially when the poet is overlooked in favour of less deserving subjects, several of whom Dunbar attacks in different poems (including the foreign alchemist whom James made an abbot, and who failed to take flight from Stirling Castle).

Two poems that address the system of patronage head on are ‘Of Discretion in Asking’ and ‘Of Discretion in Giving’ (there is a third poem in the set, called ‘Of Discretion in Taking’). The excerpts below give a sense of what the plain style looks like:

[In asking sowld discretioun be]

Of every asking followis nocht

Rewaird, bot gif sum caus war wrocht;

And quhair caus is, men weill ma sie,

And quhair nane is, it wil be thocht:

In asking sowld discretioun be.In every asking there follows no

Reward, unless there is cause

And where there is cause, men can see it well,

And where there is none, it will be thought:

In asking should discretion be.

[In geving sowld discretioun be]

To speik of gift or almous deidis:

Sum gevis for mereit and for meidis,

Sum, warldly honour to uphie,

Gevis to thame that nothing neidis.

In geving sowld discretioun be.To speak of gifts or charitable deeds:

Some give for merit, and for reward,

Some to uphold worldy honour

Give to those who need nothing.

In giving should discretion be.

How can such poems be positively – rather than negatively – characterised? Their rhetorical strategies convey directness and a moral authority – their vocabulary is relatively latinate, but it is not the kind of Latin vocabulary that is associated with aureation. Instead, we find technical religious and legal words, and few neologisms. Typical expressions include discretioun, caus, service, convenient, cure, honour, remedy and fortoun (‘fortune’). Most of these terms are well-established in the language by Dunbar’s time; many, indeed derive from Latin through French. Intermixed with such technical latinisms are blunt northernisms such as crakkis ‘boasts’, hudpyk ‘miser’ and tynes ‘loses’. The lines are short, often in tetrameter, and they have simple rhymes, here aabab, with a recurring refrain that drives home the moral point at issue. The grammatical parallelism that is characteristic of Dunbar is also evident in these poems:

Sum gevis for pryd and glory vane,

Sum gevis with grugeing and with pane,

Sum gevis, in practik, for supplé,

Sum gevis for twyis als gud agane.

In geving sowld discretioun be.Some give for pride and vainglory,

Some give with grudging and pain,

Some give for practical reasons, for their own good,

Some give to receive twice as much in return.

In giving should discretion be.

Again, we can imagine such poems as being publicly performed, or at least circulated in manuscript amongst courtiers. As we have noted, the relationship between the aggrieved poet and his patron is a delicate one: James IV was Dunbar’s social superior, and so Dunbar has to draw on a moral authority to seek to correct his behaviour and direct his patronage towards a more deserving case, namely himself. He does this by using technical, blunt language and piling up a litany of generalisations that, superficially, mask the ungenerous patron’s identity. But he can also afford a private joke at the expense of his rivals, in particular the foreign alchemist who failed in his attempt to fly from Stirling:

Sum givis to strangeris with faces new,

That yisterday fra Flanderis flew,

And to awld servandis list not se,

War thay nevir of sa grit vertew.

In geving sowld discretioun be.Some give to strangers with new faces

That yesterday flew from Flanders

And prefer not to see old servants,

Were they never of such great virtue.

In giving should discretion be.

By alluding to the preferment of his rival, and his subsequent disgrace, Dunbar is also, of course, indirectly mocking the king, who was deceived by the alchemist’s wild claims. The style may be plain, but the poems afford a rich set of insights into the culture of the early 16th century Scottish court.

Beyond the court – but supplying it with trained clerics and some of its literate nobility – were the universities. Dunbar’s alma mater, the University of St Andrews was founded between 1413-6 and was followed by the Universities of Glasgow (1451), Aberdeen (1495) and Edinburgh (1582). Their mission, structure and student population was different from those of a university today: the first three universities were originally ecclesiastical institutions that took young boys and moulded the most successful for the priesthood and for the law. The medium of instruction was Latin, and to lighten the burden of study, classical literature was taught alongside grammar, logic and rhetoric, as the basis of the university curriculum. Those who graduated with the M.A. degree were entitled to be called ‘Maister.’

Slightly older than Dunbar was the man he referred to in a poem (‘The Lament for the Makaris’) as ‘Maister’ Robert Henryson (c.1460-1500). The ‘Lament’ is largely an extended eulogy for Scottish poets who have passed away, and, as many of the names listed are unknown to contemporary scholarship, the poem indicates how much of early Scottish writing has been lost. Little is known for certain about Henryson’s life, but most scholars assume that he was associated for a time with the then new institution of Glasgow University, possibly as a regent, or tutor. It may be that, like many of his contemporaries, he had obtained his own university degree in a university on the continent of Europe. Later, he seems to have become a schoolmaster attached to Dunfermline Abbey, where, among other duties, he would have prepared boys for study in Latin at university. Together, then, Dunbar and Henryson’s work embodies the influence of university, court and church on Older Scots poetry. Although some of his poetry can be understood as political satire, Henryson’s work is generally more didactic in its nature than Dunbar’s, drawing on classical and more contemporary narratives to establish – and often to problematize – moral issues.

Henryson’s finest poetry tends to be narrative in nature. He retells Aesop’s fables, adapting them to Scottish life and politics, and adding to each tale a moral that often runs counter to the reader’s natural interpretation of the story. For example, ‘The Taill of the Cok and the Jasp’ (‘The tale of the cockerel and the jewel’) tells of a practically-minded cockerel who discovers a beautiful jewel in a dung-heap. The cock reasons, sensibly enough, that cockerels do not need jewels, and discards it. The moral coda to the fable takes the cockerel to task, likening the creature to a heathen who rejects the word of God, and aspires only to remain in the dung-heap. The moral is conventional enough, but since it is juxtaposed with the persuasiveness of the cockerel’s own sensible reasoning, the reader is forced to contrast and consider the two positions being offered – and come to his or her own opinion. In this way, they are thematically more elusive, and philosophically more provocative than most of Dunbar’s poems. And they are less obviously tied to a particular social setting – they do not assume an immediate court audience.

Henryson’s richest and most remarkable achievement is the longer narrative poem, ‘The Testament of Cresseid’. Illustrated scenes from this poem now adorn the interior of the Abbot’s House in Dunfermline. The poem gives an insight into the cultural knowledge and creative drives of a poet, immersed in classical learning, schooled in Boethian philosophy, aware of the vernacular poetry of Chaucer, and concerned about moral issues and moral instruction.

The poem serves as a sequel to Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, a tragic poem written around a century before. Chaucer’s poem is set during the Trojan War, but it draws on mediaeval narratives that embellished Homer’s epic by focusing on the love of an innocent Trojan prince, Troilus, for a more worldly Greek woman, Criseyde, or Cresseid. Chaucer’s version tells the story of the doomed lovers, their tragedy shot through with some humour, as Troilus falls in love with Criseyde, is brought together with her through the wily offices of Pandarus, and then loses her to a Greek guard, Diomede, who returns her to her own people. Troilus, grief-struck, dies in battle. Henryson endeavours to tell us what happened to Cresseid. Both Chaucer’s and Henryson’s poems served as source material for Shakespeare’s play, Troilus and Cressida.

The Scottish poet begins his story with a passage of ironic self-description that gently mocks the narrator as a dried-up old man, huddled against the wintry northern wind, and reading to try to take his mind off the cold. He takes up Boethius, and Chaucer, and then ‘ane uther quair’ (another book), which – real or imaginary – is the authority for his account of Cresseid’s fate. This account tells us that Cresseid was eventually abandoned by Diomede, and that she effectively became a common prostitute in the Greek camp. Disillusioned, she returns to live with her father, Calchas, who, appropriately, is a priest of the goddess Venus. There, she does what no character should ever do in any mediaeval Christian poem that is informed by Boethian philosophy – she complains about the unjustness of her fate, thus implicitly denying the essential goodness of providence, of God’s plan for the world. Since Henryson is writing about the pre-Christian world, Cresseid is not punished by God, but her blasphemy triggers a dream vision in which the classical gods, from Saturn to Cynthia, the moon, appear to consider her case and pass judgement. Represented by their spokesperson, Mercury, the god of Eloquence, the gods decree that the still-beautiful Cresseid should be punished by disease. Cresseid awakes from her sleep and is horrified to discover that she has been afflicted by leprosy.

Cresseid leaves her father’s home and takes up residence in a leper-house, where her condition deteriorates, and she becomes blind. She continues to complain about fate’s mistreatment of her (in an extended passage that switches stanza form and gives the reader her first-person perspective), until a chance encounter reunites her briefly with Troilus. Cresseid is begging by the road with her fellow lepers when Troilus rides by with a troop of Trojan soldiers. He sees Cresseid, but she is so deformed that he does not consciously recognise her. In a passage of considerable psychological insight, however, the image of the beggar is associated in his mind with his unfaithful lover, and he throws her his golden belt before riding on to meet (as we know from Chaucer) his eventual death on the battlefield.

Cresseid is unable to see her benefactor, but finding herself the recipient of a valuable gift, asks who the donor was. When told, she has the moment of moral insight that the narrative has been building towards: she realises that she is responsible for her own downfall, and that fate is not entirely to blame for her misery. Inspired by Troilus’ charity, she performs her first and last generous acts – the testament of the poem’s title. She bequeaths her body to the worms and toads, and gives her worldy goods to her fellow lepers She sends Troilus a ring he once gave her, and dedicates her spirit, significantly, to Diana, the goddess of chastity. She then passes away, and Troilus, who hears of her death via the messenger bearing the ring, falls in a characteristic swoon.

Henryson gives no explicit moral coda to this poem but it raises its own issues of individual moral agency in a world whose fate is determined by divine providence, or, in the pre-Christian universe of the poem, by the whims of the gods. The poem can be crudely reduced to a summary of its plot, but the text repays close reading for its stylistic confidence and richness of nuance. The stanza form of the poem is largely ‘rhyme royal’ which was used by Chaucer in his telling of the story, but it is also the stanza form used by James I in his Boethian love poem, The Kingis Quair. Much later, in 1575, the English commentator George Gascoigne describes the form (which he calls ‘rhythm royal’) thus:

Rythme royall is a verse of tenne sillables, and seuen such verses make a staffe, whereof of the first and thirde lines do aunswer (acrosse) in like terminations and rime, the second, fourth, and fifth do likewise answere eche other in terminations, and the two last do combine and shut vp the Sentence: this hath bene called Rithme royall, and surely it is a royall kinde of verse, seruing best for graue discourses.

In other words, Gascoigne shows that poets were aware of the form, which was seven lines of iambic pentameter, rhyming ababbcc, and its usual function, which was to express ‘grave discourses’. In one key passage in the poem, just before she is reunited with Troilus, Cresseid’s first person lament on her misfortunes is highlighted by being written in the ‘Complaint stanza,’ a highly complex 9-line verse form, rhyming aabaabbab. The challenge of composing a lament in verse form restricted to only two rhymes is considerable, and Henryson’s success testifies to his poetic craftsmanship:

‘O sop of sorrow, sonkin into cair!

O cative Cresseid, now and ever mair,

Gane is thy joy and all thy mirth in eird;

Of all thy blythnes now art thou blaiknit bair.

Thair is na salve may saif or sound thy sair.

Fell is thy fortoun, wickit is thy weird.

Thy blys is baneist and thy baill on breird.

Under the eirth, God, gif I gravin wer,

Quhair nane of Grece nor yit of Troy micht heird !

O morsel of sorrow, sunken into care

wretched Cresseid, now and evermore,

Gone is your joy, and all your mirth on earth;

Of all your happiness now are you stripped bare.

There is no remedy that may save or heal your sorrow

Cruel is your fortune, wicked is your fate.

Your bliss is banished, and your woe increases.

Under the earth, God, if I were buried,

Where none of Greece nor yet of Troy might

But the poem begins in rhyme royal, with a statement of its intent to disturb:

Ane doolie sessoun to ane cairfull dyte

Suld correspond and be equivalent:

Richt sa it wes quhen I began to wryte

This tragedie: the wedder richt fervent,

Quhen Aries, in the middis of Lent,

Schouris of haill gart fra the north discend,

That scantlie fra the cauld I micht defend.

A doleful season to a story full of care

Should correspond and be equivalent:

Right so it was when I began to write

This tragedy: the weather very fervent,

When Aries, in the midst of Lent,

Caused showers of hail to descend from the north

So that I scarcely could defend myself from the cold.

By looking at the etymologies and citations given in good dictionaries of Scots and English (e.g. The Dictionary of the Scots Language and the Oxford English Dictionary) we can see that many of the terms used here are Latin in origin, though they often arrived in Scots through French: correspond, equivalent, fervent. They are reminiscent of Dunbar’s plain style vocabulary of technical and formal (sometimes legalistic) terms, which were well-established in the language before the poets came to use them. A closer look at the other dictionary citations for these words shows how they were more generally used in the late 15th century. The citations suggest that the terms were indeed formal but not particularly decorous – not ‘aureate’. So we may conclude that at the start of the poem, Henryson, like Dunbar in his petitionary poems, is constructing a narrator who has some moral and intellectual authority. Henryson’s portrayal of a dried-up scholar even shares some of the irony of Dunbar’s self-fashioning as a grumpy, unjustly neglected courtier.

Henryson varies his style, however, within the poem, raising the level of aureation particularly when he comes to describe the pageant of the gods. References to Mercury, god of Eloquence, who wears a scholar’s red hood, are particularly latinate:

With buik in hand than come Mercurius,

Richt eloquent and full of rhetorie

With polite termis and delicious,

With pen and ink, to report all reddie

Setting sangis and singand merrilie;

His hude was reid, heklit atouir his croun

Lyke to a poeit of the auld fassoun.

[…]

Thus quhen thay gadderit war thir goddes sevin,

Mercurius thay cheisit with ane assent

To be foirspeikar in the parliament.

Quha had bene thair and liken for to heir

His facound toung and termis exquisite,

Off rhetorik the prettick he micht leir

In breif sermone a pregnant sentence wryte.

With book in hand then came Mercury

Very eloquent and full of rhetoric

With polite and delightful terms,

With pen and ink to report all ready

Setting songs and sining merrily;

His hood was red, fringed above his head

Like that of an old-fashioned poet.

[…]

Thus when these seven gods were gathered

They chose Mercury with one assent

To be spokesman in the parliament.

Any who had been there and wished to hear

His eloquent tongue and exquisite terms

Might learn the technique of rhetoric,

In a brief text, to write a profound deliberation.

Again, the style of the verse is not decoratively aureate in the way that Dunbar’s high-style poetry is – in the portrayal of Mercury as an old-fashioned poet-scholar, which some have also identified with Henryson himself, the poet increases the frequency of plain-style latinisms to intensify the sense of the god’s learned authority. But, as ever with Henryson, an ironic counterpoint is never far away – Mercury, no matter how learned a poet-scholar, is a false god in Henryson’s Christian universe, a dubious and unsympathetic figure who is charged with delivering to Cresseid the gods’ devastating judgement on her.

It is interesting to see how modern poets who have been drawn to updating Henryson’s poem into present-day English, have coped with the challenges of representing the Scottish poet’s intricately nuanced styles. We can look at two poets’ treatment of the following two stanzas from the judgement of Cresseid: Fred Cogswell, a highly respected Canadian poet, who published his version of the poem in 1957, and Seamus Heaney, whose version of ‘The Testament of Cresseid’ was published with adaptations of some of Henryson’s fables in 2002.

The first stanza for our consideration gives the judgement of Saturn, the eldest of the gods.

“I change thy mirth into Melancholy

Quhilk is the Mother of all pensivenes

Thy Moisture and thy heit in cald and dry

Thyne Insolence, thy play and wantones

To greit diseis; thy Pomp and thy riches

In mortall neid; and greit penuritie

Thou suffer sall, and as ane beggar die.”

In the second stanza, the narrator intrudes to comment on the story he is telling and to shape the reader’s response to the stanza just quoted:

O cruell Saturne! Fraward and angrie

Hard is thy dome, and to malitious;

On fair Cresseid quhy hes thou na mercie

Quhilk was sa sweit, gentill and amorous?

Withdraw thy sentence and be gracious

As thou was never; so schawis thow thy deid,

Ane wraikfull sentence gevin on fair Cresseid.

Fred Cogswell renders these two stanzas thus:

“Your Mirth I darkly change to Melancholy,

Which is the Mother of all thoughtfulness

Your heat and youthful blood to cold and dry;

Your insolence, your play, your wantonness

Shall all be swallowed up in sick distress;

Your pomp shall starve on crusts of beggar’s bread

And Potter’s Field shall hold you when you’re dead.”

Rough Saturn, cruel and angry God indeed,

Too hard and too malicious is your doom.

O why showed you no mercy to Cresseid

Who was so frail, so sweet, so soft a bloom?

Withdraw your verdict and give grace room

In you as never was, who by your deed

A vengeful sentence gave to fair Cresseid.

Heaney’s version, by contrast, is as follows:

“Your mirth I hereby change to melancholy

Which is the mother of all downcastness

Your moisture and your heat to cold and dry,

Your lust, presumption and your giddiness

To great disease; your pomp and show and riches

To fatal need; and you will suffer

Penury extreme and die a beggar.”

O cruel Saturn, ill natured and angry,

Your doom is hard and too malicious

Why to fair Cresseid won’t you show mercy

Who was so loving, kind and courteous?

Withdraw your sentence and be gracious –

Who never have been: it shows in what you did,

A vengeful sentence passed on poor Cresseid.

As ever, with translations, we can consider how the translators have interpreted their responsibility to be ‘faithful’ to the original – here, for example, we can ask how they have dealt with the metre and rhyme of Henryson’s poem, and what they have added and subtracted to its sense.

As far as metre is concerned, Cogswell’s rendition is the ‘smoothest’, iambic pentameter. He makes Henryson’s often irregular feet into regular iambs, thus making the poem sound more polished than the original. Heaney is less concerned to keep a regular iambic beat, and in this respect his version is closer to the rougher, speech-based rhythms of the original.

The rhyme is a continual challenge. We can compare Henryson’s realisation of rhyme royal with Cogswell’s and Heaney’s:

Henryson Cogswell Heaney

Melancholy Melancholy melancholy

pensivenes thoughtfulness downcastness

dry dry dry

wantones wantonness giddiness

riches distress riches

penuritie bread suffer

die dead beggar

angrie indeed angry

malitious doom malicious

mercie Cresseid mercy

amorous bloom courteous

gracious room gracious

deid deed did

Cresseid Cresseid Cresseid

It is evident that Henryson actually has a slightly more restricted set of rhymes in the first stanza, rhyming the final couplet with the first and third lines of the stanza. Cogswell and Heaney do not attempt to follow him in this, rhyming more conventionally ababbcc. Henryson reverts to the conventional rhyme royal scheme in the second stanza, and is again followed by the others. Henryson does not always use full rhymes, though it must be noted that Older Scots stress patterns and vowel realisations were different from those of present-day Scots. Even so, Henryson’s angrie/mercie rhyme corresponds in the final stressed vowel, but not, as it technically should, on the final stressed consonant-plus-vowel. This half-rhyming quality allows his modern translators some flexibility in rhyming practice too: even Cogswell, whose rhymes tend to be truer (just as his metre is more regular), cheats a little with the rhyme melancholy/dry.

Where Cogswell does depart more radically from the original text is in adding a biblical reference to Henryson’s lines. Henryson’s

greit penuritie

Thou suffer sall, and as ane beggar die

becomes in Cogswell’s version:

Your pomp shall starve on crusts of beggar’s bread

And Potter’s Field shall hold you when you’re dead.

The reference to ‘Potter’s Field’, which has come to be a general name for a graveyard or cemetery, comes originally, from Matthew Chapter 27:

3 Then Judas, which had betrayed him, when he saw that he was condemned, repented himself, and brought again the thirty pieces of silver to the chief priests and elders,

4 Saying, I have sinned in that I have betrayed the innocent blood. And they said, What is that to us? see thou to that.

5 And he cast down the pieces of silver in the temple, and departed, and went and hanged himself.

6 And the chief priests took the silver pieces, and said, It is not lawful for to put them into the treasury, because it is the price of blood.

7 And they took counsel, and bought with them the potter’s field, to bury strangers in.

8 Wherefore that field was called, The field of blood, unto this day.

This is likely to be a controversial addition to the original text: on the one hand it can be argued that Cogswell enhances the sense in which Cresseid is a sinner, like Judas, and is likewise buried in ‘the field of blood’; on the other hand, the reference introduces an overtly biblical allusion into a universe that Henryson seems concerned to keep explicitly pagan.

Other choices are more subtle. If you consult the Dictionary of the Scots Language online, you will find that it defines the term ‘pensiveness’ as either ‘full of thought, meditative’ or ‘full of gloom or anxious thoughts.’ To render this concept, Cogswell chooses ‘thoughtfulness’ while Heaney chooses ‘downcastness’. Henryson’s choice of expression holds both possibilities in equilibrium, or perhaps in tension. Both translators, of course, by preferring native terms to ‘pensiveness’ lose some of the latinate quality through which Henryson constructed his narrative authority.

A final point to consider is how each of the translators handles Henryson’s grammar. The trickiest negotiation is in the narrator’s impassioned outburst against Saturn – a rhetorical flourish in which the storyteller begins to harangue and command one of the characters in the story:

Withdraw thy sentence and be gracious

As thou was never.

Cogswell paraphrases these lines as:

Withdraw your verdict and give grace room

In you as never was

while Heaney presents the lines as:

Withdraw your sentence and be gracious –

Who never have been.

Neither translator quite captures the shift from command to resigned statement, ending, in Henryson’s original, with the emphatic ‘never’ before the caesura in the line. Both Cogswell and Heaney try to make the grammatical flow more standard, and the drama of the lines is reduced.

The tension between thoughtfulness and melancholy expressed by the term ‘pensiveness’ can be seen as one of the responses that Henryson must have hoped his poem would elicit. Where Dunbar’s poetry is constructed to inspire strong emotions – religious awe, or a horrified belly-laugh – or even an opening of the royal purse, ‘The Testament of Cresseid’ is designed to give the cathartic release associated with tragedy, but also to make us meditate on the mysteries of providence and the role of individual agency.

Together, then, the poetry of Henryson and Dunbar testify to the richness of cultural life in Scotland, in and beyond the royal court, at the end of the fifteenth century and the beginning of the sixteenth. Sadly, much of the evidence of that culture has now been lost, as is shown by Dunbar’s ‘Lament for the Makaris,’ his eulogy naming a series of Scottish poets whose work is now unknown. Poetry in early 16th century Scotland still tended to circulate in manuscript amongst the small coteries of the literate, only occasionally achieving wider fame. But things were changing.

In 1508, probably a few years after Henryson’s death, and only five years after Dunbar celebrated in verse the marriage of James IV to Margaret Tudor, Chepman and Myllar set up the first printing press to be used in Scotland. Its main purpose was to publish laws and administrative texts, but the printers also distributed poems by Henryson and Dunbar. These early books are available to view on the National Library of Scotland’s website, devoted to ‘The First Scottish Books’. Print, of course, eventually made written texts available to a mass audience – and in the 16th century it would fuel a religious and political revolution that engulfed all of Europe. This challenge to the centuries-old institution of the Catholic Church became known as ‘the Reformation’. As we see in the next chapter, Scotland would not be immune to its effects.

Further reading and Links

Two concise introductory guides to Dunbar and Henryson are:

Baird, G (1996) The Poems of Robert Henryson. Glasgow: ASLS

Jack, RDS (1997) The Poetry of William Dunbar. Glasgow: ASLS

The modern versions of ‘The Testament of Cresseid’ are

Cogswell, Fred (1957) ‘The Testament of Cresseid’ by Robert Henryson. Toronto: Ryerson Press

Heaney, Seamus (2009) Robert Henryson: The Testament of Cresseid and Seven Fables London: Faber & Faber

Links to online editions of the poetry and to relevant sites are:

Dunbar, William (2004) The Complete Works, ed. J. Conlee.

Henryson, Robert (2010) The Complete Works, ed. D.J. Parkinson.

Henryson, Robert ‘The Testament of Cresseid’. Annotated edition

National Library of Scotland (2006) Scotland’s First Books