As we saw in the previous chapter, Sir Walter Scott’s extraordinary success as an author changed the literary landscape of the early 19th century. Fiction replaced poetry as the primary literary form; an increasingly literate society made mass market publishing feasible for fiction in the form of novels, which were often serialised in magazines; and Scott’s historical romances fashioned an international taste and demand for Scottish narratives, landscapes and characters.

The impact of Scott on Scottish publishing in the first half of the 19th century can be seen in the proportion of British novels published in Scotland, decade by decade. As Bill Bell has shown, between 1800 and 1810 only 0.5% of British novels were published in Scotland. With the publication of Waverley in 1814, there was a leap in production, and between 1810 and 1820, 4.4% of British novels were produced north of the border. The peak years were 1822-25 when no less than 15% of all British novels were published in Scotland; then a stock market crash caused a financial panic that, as we saw in the previous chapter, threatened to ruin Scott, and damaged Edinburgh’s position as a leading publishing centre.

The thirst for Scottish themes, however, continued unabated amongst the reading public, and one of the beneficiaries of the fashion for Scottish topics was John Galt (1779-1839). Born in Irvine, on the west coast of Scotland, and son of a naval captain, Galt grew up in Scotland and England, where he found work as a junior clerk, and started writing journal articles on commercial topics. He later studied law, and travelled on the European continent, befriending the poet, Byron, whose biography he later wrote. His earlier publications included several biographies, including one, published in 1816, of the American-born painter Benjamin West, who later became President of the British Royal Academy.

West was known for portraying historical scenes – one of which, painted between 1771 and 1772, depicted the making of a treaty between William Penn, founder of Pennsylvania, and local Native Americans. It is worth looking at in connection with Galt, since its concerns mirror those of the Scottish novelist and other writers who were influenced by the Scottish Enlightenment. To the left of the portrait stands a group of men in European costume, at the centre of which is Penn, in Quaker dress. Before Penn, two European males kneel, one of whom is presenting a bale of cloth to an Indian chief. Around the chief, to the right, several members of the tribe are gathered, and to the far right, a squaw suckles a child.

It is clear – and widely observed – that the composition of the painting resembles a secular nativity scene, with the bale of cloth at the core of the image substituting for the infant Christ. The figures of the Quaker colonist and the Native American Madonna and Child reinforce the religious allusion. Viewed in this way, the painting elevates commerce to a spiritual calling. Finished at the very time Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, and prefiguring Walter Scott’s ‘The Two Drovers’, West’s painting is another vision of cross-cultural engagement facilitated by the power of trade. Peaceful relationships between the two civilisations, European and Native American, are enabled by the barter of cloth: that, at least, is the promise. As Scott, and later history, showed, the market is no guarantee of stable, harmonious relations between cultures. Even so, a concern with the development of civilisation, and the presentation of the forces of social history, however, were to continue to mark John Galt’s career when he turned from commercial writing, memoirs and biography, and began to write novels.

Galt’s first novels, The Annals of the Parish and The Ayrshire Legatees were published in 1821, at the beginning of the peak years for Scottish publishing in the first half of the 19th century. It is likely that he benefited from the fashion for Scottish subject matter that allowed publishers to take a risk with a one-volume novel that presented itself as the annual diary of the Reverend Micah Balwhidder, the minister of a small parish in the west of Scotland, over 50 years, from 1760-1810. The success of these novels allowed him to continue developing his portrayals of small-town Scottish life in later books like The Provost (1822), another first-person account of a burgh official, and the more ambitious three-volume family saga, The Entail (1822).

As well as developing a career as a novelist, Galt became actively engaged in British colonial trade and administration. In 1824 he was appointed Secretary of the Canada Company, and he lived and worked in Canada, establishing the city of Guelph, Ontario in 1827. However, in 1829, he was accused of misadministration, and he was forced to return to Britain, spending some months in prison for debt – two later novels, Bogle Corbet (1831) and The Member (1832) directly address, respectively, the experience of Canadian settlers, and Galt’s satirical views of political corruption in Britain. By the time he published them, Galt was working again for the British American Land Company, but he retired in 1832 for reasons of ill health, and he returned to Greenock on the west coast of Scotland, where he continued to write and publish until his death in 1839.

Galt, then, was a Scottish novelist who was actively engaged in commercial activities in the international sphere – like William Penn and his countrymen in West’s portrait, he travelled to the new world to engage in trade. And as a novelist, he was, from the beginning, fascinated by the process by which so-called ‘primitive’ cultures, like those of West’s Native Americans, became ‘civilised’ cultures, like those of Penn and his fellow Europeans. This process is one that underlies the otherwise episodic events of The Annals of the Parish, which, as Galt described it, was intended as ‘a kind of treatise on the history of society in the West of Scotland during the reign of George the Third.’ This was the reign in which Scotland, too, arguably, had moved rapidly from primitive to civilised society.

The inevitable progress of civilisation had also piqued the interest of the Scottish Enlightenment philosophers active in Edinburgh in the last quarter of the 18th century. One of those philosophers, Dugald Stewart, who was present at the meeting between Burns and the young Walter Scott, mentioned in Chapter 7, framed the question as follows in the 1790s:

When, in such a period of society as that in which we live, we compare our intellectual acquirements, our opinions, manners, and institutions, with those which prevail among rude tribes, it cannot fail to occur to us as an interesting question, by what gradual steps the transition has been made from the first simple efforts of uncultivated nature, to a state of things so wonderfully artificial and complicated.

The Collected Works of Dugald Stewart, ed. Sir William Hamilton, 10 vols. (Edinburgh, 1858), X, pp. 32-34

To put it another way, what ‘gradual steps’ would account for the ‘transition’ from being a ‘rude tribsman’ or a rural Scot to the ‘wonderfully artificial and complicated’ state of urban civilisation? As Keith Costain has argued in detail, to answer this question, Stewart and his fellow philosophers , including Adam Ferguson and Adam Smith, developed the notion of ‘theoretical’ or ‘stadial’ history, or the ‘invisible hand’ of progress. Costain shows that Galt took up Stewart’s notion, even echoing Stewart’s phrase, ‘theoretical history’, and The Annals of the Parish in particular can be read as Galt’s dramatization of the unseen processes of history in action.

Theoretical historiography was practised by Scottish Enlightenment philosophers from Adam Ferguson (An Essay on the History of Civil Society, 1767) to James Mill (A History of British India, 1817). Characteristically, theoretical historians suggest that historical events have natural, hidden causes that lead inevitably to progress – these causes are, significantly, not ascribed to the overt, rational plans of individuals or to the outcomes of explicit national policies. The ‘gradual steps’ that account for the transition from primitive barbarism to wonderfully artificial ‘civilisation’ can be broadly described as the transformation from hunting, to pasturage, to agriculture, to commerce and industry. Benjamin West’s portrait of the treaty between Penn and the Native Americans, then, can be seen in geographical terms as an encounter between ‘rude tribespeople’ and ‘civilised Europeans’, but it can also be seen in chronological terms as the civilised present meeting its primitive past.

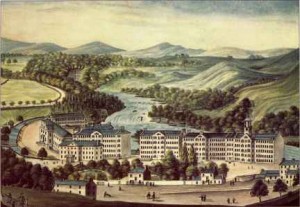

Galt’s The Annals of the Parish has at its core the gradual transition between the last two stages of civilised progress, namely, from agriculture to commerce and industry. The novel begins with the arrival of the young minister, Micah Balwhidder, in the rural parish of Dalmailing in the west of Scotland, in 1760, the year in which he begins his diary. Over the next fifty annual entries, we cover the invention of the spinning jenny (1764) and the consequent rise of the cotton industry, the American revolution of 1776 (which is also the year of the publication of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations) and the loss of the American colonies, the rise of the second British Empire in India (1783), the French revolution of 1789-99, the rise of Napoleon (1799) and the French threat to invade Britain (1803).

Over this period, these international events are seen to impact upon the small Scottish parish, which sees itself equally transformed by the rise of industrialisation, represented by the establishment of a nearby mill-town, the import of radical ideas amongst the cotton-workers, and the loss of older ways of thinking and behaving.

The choice of a rural minister as the witness to the inevitable march of progress indicates Galt’s ironic sensibility, which is generally gentle but has a sharp edge. In his Essay on Civil Society (1767), Adam Ferguson had argued that

…every step and every movement of the multitude, even in what are termed enlightened ages, are made with equal blindness to the future; and nations stumble upon establishments, which are indeed the result of human action, but not the execution of any human design.

Ferguson stresses – again – that individuals may contribute to progress, but accidentally, not by design. This point is taken up by Adam Smith, whose account of the ‘invisible hand’ of progress has been described as a form of ‘secularised Providence’ (Costain, p. 346). Smith notes that man, who intends only his own gain through his trading activities, ends up ‘promoting an end that was in no part his intention’. The unintended moral agency ascribed to trade and commercial activities recalls once again the quasi-religious composition of West’s portrait of Penn and the Native Americans. And the dissonant combination of material and spiritual aspirations informs the ironic perspective of Micah Balwhidder in The Annals of the Parish.

Micah is, of course, a religious man, and he frequently credits ‘Providence’ with the gradual improvement of conditions in the parish that he serves. However, one of the running jokes in the novel is that Micah also manages to make his own life materially much more comfortable, mainly through two good marriages. Micah’s first wife secures his good standing in an initially hostile local community, and after she passes way, his second wife works hard to earn additional income that adds considerably to the family’s financial wellbeing. As Micah makes his annual observations on events in his parish, we gradually come to see what kinds of person and event promote beneficial progress and what acts as an obstacle to the advance of civilisation.

The obstacles to progress come from the extreme ends of political ideology, those whose political beliefs are similar only in that they mistakenly believe they can influence the march of history. On the one hand, the French revolutionaries, Napoleon, and the local radicals they inspire, all act to disrupt society and so impede progress. At the opposite end of the political spectrum, the reactionary conservatives seek to protect their own vested interests – here, the landed gentry oppose the establishment of the cotton-mill that threatens their future but which provides employment and increased wealth for the population at large.

Galt subscribes to the vision of a progressive society as one that is both stable in its political institutions, and open to change. Its members balance self-interest with generous and practical concern for the well-being of others. The Annals of the Parish is populated by characters who represent both enlightened self-interest (Micah himself; Messrs Coulter and Kibbock, agricultural improvers; and Mr Cayenne, the founder of the cotton mill), and those whose blind greed threatens the advance of civilisation (Major Gilchrist, a returning ‘Nabob’ who has made his fortune in India; Mr Speckle, an irresponsible capitalist; and Mungo Argyle, a murderous tax-collector).

Costain (p. 360) argues that Micah himself grows in understanding about the dynamics of his small community:

[Balwhidder] is entirely conscious of the connections he draws between the coming of the cotton mill and the development of Dalmailing from the status of a “clachan” to that of a town; between the French Revolution and the growing class antagonisms and sectarianism in Dalmailing; and between the French upheaval, the rise of industry, and the growing secularism of his people which he observes with dismay until the Napoleonic wars help to bring them back to the kirk.

This is, however, a moot point. Galt’s ironic strategy is one of the first-person narrator’s unconscious self-revelation – Micah sees the changes in his society and articulates them, but he often mis-ascribes the ‘invisible hand’ to a creator that many Enlightenment philosophers would have quietly been sceptical about. It takes the knowledgeable reader to understand Micah’s limitations and to reframe the diary entries in the context of post-Enlightenment ideas.

Meanwhile, part of the charm of the novel lies in Galt’s careful attention to detail, from the impact of improved modes of transport on the growing village’s integration into the wider world, to the changing attitudes to the consumption of tea in the parish, and eventually even in the manse. And a large part of the charm is in the ironic but sympathetic construction of the character of Micah himself – he is slightly pompous but essentially generous, spiritually oriented but professionally proud, and self-interested yet genuinely caring for his ‘flock’. He is seen also through the relationships with his two wives and his children, a daughter who turns out to be a ‘cultivated’ member of polite society, and a son who grows into a rather corpulent member of the merchant class.

After The Annals of the Parish, Galt went on to publish some other volumes in a similar vein, the ironic self-revelations of a small-town Machiavelli in The Provost and two of the earliest political novels in English, The Member and its sequel, The Radical. Galt wrote three-volume novels on other topics too – The Entail is a family saga about the consequences of an obsession for land, and Ringan Gilhaize addresses the more distant past in its account of the Covenanting wars of the 17th century. But it is on the one-volume novels of ironic self-revelation that Galt’s reputation largely rests: they helped establish a genre of 19th century fiction that dealt with provincial life and social and political change. From these beginnings we can see the seeds of later ‘Condition of England’ novels of the 1840s and 1850s, and even English novels like George Eliot’s Middlemarch: A Study of Provincial Life (1871-2). All of these novels take a local place as a microcosm of wider society, and explore the impact of political and social changes on the characters. As Galt himself observed:

I do not think I have had numerous precursors, in what I would call my theoretical histories of society, limited, though they were required by the subject, necessarily to the events of a circumscribed locality.

In The Annals of the Parish and its successors, the ‘circumscribed locality,’ whether it was a fictional Scottish village or English Midlands town, became a laboratory for understanding the broader processes of historical change.

Further reading and links

Bell, B. (2007) The Scottish Book Trade at Home and Abroad. In Brown, I. (Ed.). The Edinburgh History of Scottish Literature: Enlightenment, Britain and Empire, 1707-1918. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 221-227.

Costain, K. M. (1976). Theoretical History and the Novel: The Scottish Fiction of John Galt. ELH, 43(3), 342-365.

E-books by John Galt are available from the Project Gutenberg website at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/588