In this chapter we explore the changing functions of literature and the changing roles of poets in the 18th century. At the beginning of this century, we move into period of Modern Scots and as the decades pass, we begin – gradually – to see the contemporary figures of the poet, the novelist and the dramatist emerge.

As we saw in the previous chapter, Scotland again underwent radical social and political changes in the last decades of the 17th century, and these changes impacted on its literature. The main space for literary activity had been the court – and with the removal of the court to London at the start of the 17th century, the space for a distinctively Scottish court literature was closed. We saw that, for example, Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty wrote first for the London-based court of Charles I, and then, after the king’s execution, for his republican successors. His works are largely in English. In Scotland, however, ballads, songs and folk tales continued to be performed in Scots and Gaelic; and towards the end of the century these began to be written down.

The republican Commonwealth eventually gave way to the restored monarchy of Charles II, who died in 1685, to be succeeded by his brother, James II and VII. Around this time several momentous events occurred. First, James II converted to Roman Catholicism and, on the birth of his son, James Francis Edward Stuart in 1688, there was an openly Catholic heir to the throne of the United Kingdom. Protestant forces opposed to a Catholic monarchy forced James into exile in France, replacing him with his daughter, Mary, who was married to the Protestant, William of Orange.

The accession of William and Mary to the throne of the United Kingdom is known as the ‘Glorious Revolution’. James and his son remained in exile in France, and they plotted to regain control of the kingdom; supporters of their cause were known as Jacobites. When James II died in 1701, his son and then his grandson, Charles Edward Stuart or ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’, continued to campaign to be restored as king. Sympathy for the Jacobite cause was particularly strong in the highland areas of Scotland.

In the 1690s, many of the wealthier Scottish families were tempted to invest money in a scheme to colonise part of the Panama peninsula, a place called Darien, and so establish a Scottish colony that would be well placed to benefit from trade routes between the Atlantic and Pacific. It is estimated that around half of the national wealth of Scotland was invested into the Darien scheme; owing to various factors, including internal disputes, hostility from existing colonial powers such as Spain and England, and the difficulties of coping with the local climate, the colony failed and the investors lost their investments. The dawn of the 18th century, then, saw Scotland suffering the loss of the Stuart monarchy, and in the midst of a deep financial crisis.

The solution, for Scotland and England’s political elites, was a more thorough political and economic integration between the two nations. A Treaty of Union was negotiated and, in the face of popular opposition, in 1707, the treaty was ratified by separate Acts of Union in Scotland and England. The state of Great Britain was formed. Many of the debts incurred by the Darien disaster were paid off, and the Scots agreed, in an Act of Settlement, that the Protestant Hanoverian descendants of William and Mary would be accepted as legitimate monarchs of the UK. The separate Scottish parliament was disbanded and absorbed into the Westminster parliament in London.

In the early 18th century, as a response to this perceived loss of Scottish sovereignty, there was a rise in cultural nationalism. In the early 1700s, around the time of the Treaty of Union, a revival of interest in literature in Scots was signalled by book publications such as James Watson’s Choice Collection of Comic and Serious Scots Poems both Ancient and Modern (1706-1711) and Thomas Ruddiman’s edition of Gavin Douglas’ 16th century Eneados (Æneid) in 1710.

These book publications indicate a growing middle class readership for Scottish texts; at the cheaper end of the market, a new industry in cheap, one-page ‘broadside’ publications was also beginning to flourish. The broadsides were originally official public proclamations, but by the early 18th century their content had broadened out to include songs, satirical poems, and versions of topical events, such as the speeches supposedly given by condemned prisoners before their execution. In some cases, the language used in the broadsides was Scots. It is likely that broadsides appealed to readers with perhaps limited literacy, or to labouring-class readers who enjoyed performing them to a less literate audience.

Another space for the performance of literature in Scots – songs and satirical poems, for example – was the local club or association. As the historian Linda Colley has observed, clubs were a notable feature of 18th century life:

Voluntary associations of different kinds were breaking out like measles over the face of Britain and the rest of Europe at this time, especially in towns, and almost exclusively among men. There were street clubs, patronised by the leading inhabitants of a particular district, clubs devoted to hobbies, everything from rose-growing to cruel sports and idiosyncratic sex, innumerable masonic and quasi-masonic societies catering to the male delight in secret rituals and dressing up, box clubs, which poorer men joined to provide themselves with a modicum of insurance, clubs devoted to party politics or food, discussion clubs where blue-chinned autodictats pondered the mysteries of science and philosophy, and more genteel associations where responsible citizens met to dine well and discuss the local poor.

(Linda Colley, Britons: The Forging of the Nation 1992; p.88)

Clubs provided a space for self-improvement and political dispute; they also provided an immediate audience for literary composition, orally performed or circulated in manuscript. Broadside printing or even book publication might later follow. This seems to be the route taken by the first substantial poet to work in Scots after the Union, Allan Ramsay (1686-1758).

Ramsay moved from the Scottish borders to Edinburgh as a young man, and became established in the city first as a wig-maker. By 1712 he was a member of small group of associates who shared literary interests, the Easy Club, in which he adopted the alternating pseudonyms of Gavin Douglas, after the Scottish poet and translator, and Isaac Bickerstaff, after the author of the London magazine The Tatler (itself in fact a pseudonym for the Irish writer, Sir Richard Steele). The fact that Ramsay adopted two pseudonyms is perhaps suggestive of his perception of himself as being heir to two traditions. A sense of the literary and social activities of these clubs can be gained by examining a selection of their minutes, e.g the following entry for 1715

13 April 1715

Two poems were presented by Gawin Douglas [ie Allan Ramsay] One upon the Debate or discourse in ye club ye 16 of March about the Requisites necessary to Constitute a Gentleman.

Ramsay began to develop a literary career, publishing some of his verse first in broadsides, and then in a collected edition of 1721. ‘Lucky Spence’s Last Advice’ is a good example of the way in which literary texts were disseminated to different audiences. This satirical ballad, which ostensibly gives a real-life brothel-keeper’s last words to her working girls, probably began as a performance piece for a few friends, then surfaced in print as an anonymous broadside, probably around 1718, before ending up in book form .The advice is written in light Scots, e.g.

Wi well crish’d Loofs I hae been Canty;

Whan e’er the Lads wad fain a faun t’ye,

To try the auld Game Taunty Ranty,

like Cursers keen,

They took Advice of me your Aunty

if ye was clean.

With well-greased palms, I have been merry;

Whenever the lads would like to have fallen to you

To try the old game of ‘rumpy pumpy’

Like stallions keen,

They took advice from me, your Auntie

[To know] if you were clean.

To balance the bawdier verses, Ramsay also includes in his Poems translations of the Latin poet, Horace, although, as he revealingly admits in his Preface, he is not classically trained:

I understand Horace but faintly in the Original, and yet can feast on his beautiful Thoughts dress’d in British; and do not see any great occasion for every Man’s being made capable to translate the Classicks, when they are so elegantly done to his hand.

The admission is significant because once again it demonstrates Ramsay’s relative lack of education (though literacy rates in Scotland as a whole at this time were still low compared to the present day), and because it shows him asserting a ‘British’ identity for English as a medium of translation. His version of Horace’s ode (I.v) addresses another young female beauty who is out to ensnare a man:

What young raw muisted beau bred at his glass perfumed

Now wilt thou on a rose’s bed carress?

Wha niest to thy white breasts wilt thou intice, next

With hair unsnooded and without thy stays?

O bonny lass, wi’ thy sweet landart air, rustic

How will thy fikle humour gie him care.

When’er thou takes the fling-strings, like the wind

That jaws the ocean, thou’lt disturb his mind. dashes

When thou looks smirky, kind and claps his cheek:

To poor friends then he’l hardly look or speak.

The coof believes’t na, but right soon he’ll find fool

Thee light as cork, and wav’ring as the wind.

On that slid place where I ’maist brake my bains, slippery, bones

To be a warning I set up twa stains, stones

That nane may venture there as I hae done,

Unless wi’ frosted nails he clink his shoon. hammer, shoes

It is worth reflecting on possible reasons for the appropriation of Horace’s Latin odes into literature in Scots during this period. Horace (65-8 BC) adopted a stance that privileged country life amongst a small circle of friends to the corruption of the metropolis, and in many of his odes he extolled the virtues of epicureanism, or the pursuit of pleasure. This was an attractive model for Scots in Edinburgh who found themselves no longer in a national but a provincial capital, removed from the metropolis of London. They could take satisfaction from a pleasant life in a convivial company whose members share the poet’s values – in his poem attacking the fickle ‘bonny lass’ who ensnares her lovers, the poet ends by setting up a warning sign for the benefit of others who might be seduced by her charms. It is again the kind of poem that might be performed in a social group largely composed of young men.

Ramsay went on to update and edit collections of Older Scots poetry, in anthologies like The Ever Green, and he established a reputation as a dramatist with his pastoral drama, The Gentle Shepherd (1725). He therefore stands as a pivotal figure, linking the older tradition of literature in Scots with the new, revived vernacular tradition that is emerging from performance, broadsides and book publication amongst the aspiring middle and professional classes in the 18th century.

Eight years before Ramsay’s death, the second poet to be considered in this chapter was born, Robert Fergusson (1750-1774). Of the three poets considered here, Fergusson was the only one to attend university, the University of St Andrews, where he began writing poetry, mainly in English. He had to return to the family home in Edinburgh on the death of his father, and take up a post as a lawyer’s clerk. Like Ramsay and, later, Burns, Fergusson was a member of a club, the Cape Club, and we can imagine a situation in which he began performing poetry in this convivial context. In 1771, he started publishing Scots verse on local and topical matters in an early newspaper, the Weekly Review, which had been established by Walter Ruddiman, Thomas Ruddiman’s nephew, three years earlier. The response to Fergusson’s Scots poetry was sufficiently enthusiastic for Ruddiman to publish a collection in the form of a book, in 1773, a year before the poet’s untimely death.

Fergusson’s poetry shares some of its general characteristics with Ramsay’s: it is at heart clubbable verse, written by a young man in the Scottish capital city for his fellow citizens. Like Ramsay, he draws upon Horace’s verse and translates a poem on the theme of carpe diem, or the importance of ‘seizing the day’:

Horace, Ode XI. Lib I, by Robert Fergusson

Ne’er fash your thumb what gods decree trouble yourself

To be the weird o’ you or me, fate

Nor deal in cantrup’s kittle cunning witchcraft’s mysterious

To speir how fast your days are running. ask

But patient lippen for the best, trust

Nor be in dowy thought opprest, gloomy

Whether we see mare winters come

Than this that spits wi’ canker’d foam.

Now moisten weel your geyzen’d wa’as dried-out

Wi’ couthy friends and hearty blaws; sociable

Ne’er let your hope oe’rgang your days, over-reach

For eild and thraldom never stays; age, servitude

The day looks gash, toot aff your horn, bright, drain your cup

Nor care yae strae about the morn. give a care, tomorrow

Like Ramsay, Fergusson integrates literate culture (here the classical source is in the form of a sonnet) with orality. His vocabulary draws on popular oral formulae (e.g. ‘ne’er fash your thumb´, ´toot aff your horn’ and ‘care you strae’) to domesticate the classical source, turning the Latin poet into a contemporary fellow speaker of Scots. The original poems he writes continue to value the homely, the native and the convivially social. In many of his poems, the themes and treatment anticipate Burns’ later work, which echoes even Fergusson’s phrases. Fergusson’s ‘Braid Claith’ employs the ‘Standard Habbie’ folk stanza that Ramsay also used, to proclaim, with evident irony, the virtues of being clothed in the finest broadcloth:

Braid Claith lends fock an unco heese, folk, considerable lift

Makes mony kail-worms butterflies, cabbage-worms

Gies mony a doctor his degrees gives

For little skaith: harm

In short, you may be what you please

Wi’ gude Braid Claith.

One of Fergusson’s few pastoral poems, ‘The Farmer’s Ingle’, less ironically praises the homely virtues of rustic life, elevating the theme by using the stanza form first associated with Spenser’s epic The Faerie Queene, and more recently revived by the English poet, William Shenstone, to describe, in a mock-heroic manner, a village teacher, in ‘The School-mistress’. Fergusson’s poem is gently affectionate:

The fient a chiep’s amang the bairnies now; not a sound’s, children

For a’ their anger’s wi’ their hunger gane: gone

Ay maun the childer, wi’ a fastin mou’, must , mouth

Grumble and greet, and make an unco mane, loud complaint

In rangles round before the ingle’s low: multitudes, flame

Frae gudame’s mouth auld warld tales they hear, wife, old world

O’ Warlocks louping round the Wirrikow, leaping, hobgoblin

O’ gaists that win in glen and kirk-yard drear, ghosts,

Whilk touzles a’ their tap, and gars them shak wi’ fear. makes their hair standon end

This kind of scene must have been familiar to Robert Burns (1759-96), who grew up in a farming household in Ayrshire, and who later revisited the theme, more sentimentally, in his own poem ‘The Cottar’s Saturday Night’, which again uses the Spenserian stanza to affirm the worth of the apparently lowly subject matter. Fergusson’s status as a poetic precursor to Burns, who publicly acknowledged his debt to his ‘elder brother in the Muse’ has tended to overshadow his own considerable poetic talents, especially as a chronicler of city life in Edinburgh, as in his most ambitious poem, ‘Auld Reekie’.

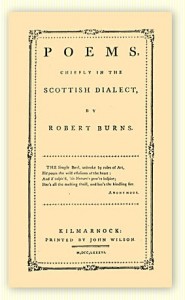

Burns took the now familiar route to publication, joining a club as a young man (the Bachelors’ Club in the village of Tarbolton), circulating some of his earlier poems in broadside, and then collecting a number of them in a book. Burns’ first volume of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, known generally as the ‘Kilmarnock edition’ was published in a limited print run in 1786. Despite having a small circulation, the Kilmarnock edition was positively reviewed, and its contents liberally quoted from in the periodical literature of the time, which was becoming ever more influential.

As a result of glowing notices in some English magazines, Burns suddenly found himself a literary celebrity and he visited Edinburgh where he cultivated the image of ‘the ploughman poet’ and was duly lionized by polite society. There, he arranged for a further, expanded edition of his poems to be printed by the main publisher in the capital, William Creech.

He eventually left Edinburgh, first to lease a farm in Dumfries, and, when that failed, to work as an excise officer in the region. In this period, He became deeply involved in collecting, revising and composing Scottish songs for publication in anthologies such as George Thomson’s A Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice and James Johnson’s The Scots Musical Museum. While his literary enterprises were successful, Burns made relatively little profit by them – letters and poems chronicle his battles with Creech to obtain his due for the editions of his poems, and he contributed to the song anthologies for little or no recompense.

Burns also was notoriously attracted to romantic entanglements; as a young man he was publicly chastised by the local Presbyterian church for his sexual conduct (he had his first daughter by one of his family’s servants, Elizabeth Paton); and he later entered enthusiastically into relationships with a number of women, including a passionate ‘textual affair’ with Agnes, or ‘Nancy’ McLehose, an Edinburgh woman separated from her husband, and who aspired, herself, to be a poet.

Burns managed to indulge a heated correspondence with Nancy while getting her maid, Jenny Clow, pregnant. He later married Jean Armour, who bore him nine children of their own. Only three of the children born to Jean Armour and Burns survived beyond infancy, but Jean also cared for several of Burns’ offspring by other women, including Jenny Clow, and a maidservant, Margaret Cameron.

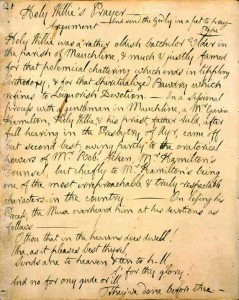

It is evident from this brief biographical sketch that Burns had a tremendous appetite for life, and his passionate engagement with politics, philosophy, companionship and love are everywhere evident in his poetry. One of his earlier satirical poems was no doubt performed in small circles before achieving local notoriety in broadside form. It was not published between the covers of a respectable book for some time. The poem is called ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer,’ and it springs from a dispute between a conservative elder in Mauchline parish church, William Fisher, and a more progressive lawyer who happened to be amongst Burns’ friends.

Burns’ poem undermines Fisher’s credibility by portraying him as a religious and moral hypocrite who adheres to the Presbyterian doctrine of ‘justification by faith’. Simply put, this doctrine held that God had pre-determined the number of humans who would be saved and go to heaven, and those who would be damned and go to hell. The doctrine held that the number of the damned would greatly outnumber that of the saved, and, moreover, since the decision was pre-determined, no action by humans could change it. Thus those who were saved (a group known as ‘the elect’) would go to heaven, not for any good actions they had performed, but because they had faith in God. And God would grant the elect knowledge of their ‘election’ to the ranks of the saved.

Burns saw the potential of this doctrine to fuel religious hypocrisy, and ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’ begins with the church elder addressing God, describing justification by faith, and thanking Him for making him one of the elect. As the poem continues, the elder’s various sins – including fornication and drunkenness – are gradually revealed:

From ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’

O thou, wha in the heavens dost dwell,

Wha, as it pleases best thysel’,

Sends ane to heaven, and ten to hell,

A’ for thy glory,

And no for ony gude or ill

They’ve done afore thee!

I bless and praise thy matchless might,

Whan thousands thou hast left in night,

That I am here afore thy sight,

For gifts and grace,

A burnin’ and a shinin’ light

To a’ this place.

What was I, or my generation,

That I should get sic exaltation,

I wha deserve sic just damnation,

For broken laws,

Five thousand years ‘fore my creation,

Thro’ Adam’s cause.

When frae my mither’s womb I fell,

Thou might hae plunged me in hell,

To gnash my gums, to weep and wail,

In burnin’ lake,

Whar damned devils roar and yell,

Chain’d to a stake.

Yet I am here a chosen sample;

To show thy grace is great and ample;

I’m here a pillar in thy temple,

Strong as a rock,

A guide, a buckler, an example,

To a’ thy flock.

But yet, O Lord! confess I must,

At times I’m fash’d wi’ fleshly lust;

And sometimes, too, wi’ warldly trust,

Vile self gets in;

But thou remembers we are dust,

Defil’d in sin.

O Lord! yestreen thou kens, wi’ Meg—

Thy pardon I sincerely beg,

O! may’t ne’er be a livin’ plague

To my dishonour,

An’ I’ll ne’er lift a lawless leg

Again upon her.

In this satire, Burns uses a rich, colloquial Scots turn of phrase, and the popular rhyme scheme – ‘standard Habbie’ – that had been taken up and popularised in similar satires by Ramsay and Fergusson. Burns, however, took both the language and the stanza form and turned it to very different purposes in other poems, notably ‘To a Mouse’, the poem that fixed his image as ‘the ploughman poet’. In this poem he imagines himself at the plough, overturning a mouse’s nest, and then addressing the creature, not satirically, but sympathetically, as a vulnerable fellow creature. The ploughman first apologises to the startled animal, and then engages it in philosophical reflection.

To a Mouse

Wee, sleekit, cow’rin’, tim’rous beastie,

O, what a panic’s in thy breastie!

Thou need na start awa sae hasty,

Wi’ bickering brattle!

I wad be laith to rin an’ chase thee,

Wi’ murd’ring pattle!

I’m truly sorry man’s dominion

Has broken nature’s social union,

An’ justifies that ill opinion,

Which makes thee startle

At me, thy poor earth-born companion,

An’ fellow-mortal!

I doubt na, whyles, but thou may thieve;

What then? poor beastie, thou maun live!

A daimen icker in a thrave

‘S a sma’ request:

I’ll get a blessin’ wi’ the lave,

And never miss’t!

Thy wee bit housie, too, in ruin;

Its silly wa’s the win’s are strewin’!

An’ naething, now, to big a new ane,

O’ foggage green!

An’ bleak December’s winds ensuin’,

Baith snell and keen!

Thou saw the fields laid bare an’ waste,

An’ weary winter comin’ fast,

An’ cozie here, beneath the blast,

Thou thought to dwell,

’Till, crash! the cruel coulter past

Out thro’ thy cell.

That wee bit heap o’ leaves an’ stibble,

Has cost thee mony a weary nibble!

Now thou’s turn’d out, for a’ thy trouble,

But house or hald,

To thole the winter’s sleety dribble,

An’ cranreuch cauld!

But, Mousie, thou art no thy lane,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men,

Gang aft a-gley,

An’ lea’e us nought but grief and pain,

For promis’d joy.

Still thou art blest, compar’d wi’ me!

The present only toucheth thee:

But, Och! I backward cast my e’e,

On prospects drear!

An’ forward, tho’ I canna see,

I guess an’ fear.

It has been widely observed that the faux-naïf self-portrait of the sensitive ploughman in fact draws on sophisticated theories of moral philosophy current in Burns’ lifetime, in particular The Theory of Moral Sentiments published by Adam Smith in 1759, the year of Burns’ birth. Smith can be seen as the direct source of the picture of the natural universe as a ‘social union’ – a benevolent commerce between creatures that has been inadvertently broken by the careless farmer. The ploughman thus asserts solidarity with the animal, suggesting that both ‘mice and men’ often share the misfortune of having their best-laid plans going awry. These lines, of course, were taken up in the 20th century by John Steinbeck who alluded to them in the title of one of his most famous novels.

Burns’ poem concludes, poignantly, by suggesting that in fact men have a greater misfortune than animals, in that animals have no consciousness of pain beyond the present moment, while people are aware of past disappointments and future anxieties. The poem is a controlled blend of noble sentiment and powerful reflection, in which Burns moves effortlessly back and forth between Scots and English.

Burns’ published poems, then, included comic verses, biting satires, celebrations of Ayrshire life, and – a later poem – the glorious comic narrative, ‘Tam O’Shanter’, the mock-epic story of a friend’s drunken ride home from Ayr to Alloway, during which he encounters a coven of witches, and the very devil playing the bagpipes.

But in Burns’ later years he became increasingly involved in collecting, often revising and composing songs. He contributed songs to several anthologies of Scottish song, also suggesting traditional tunes to which they may be sung. One of his most famous was a version of a traditional song, transmitted orally. Burns first contributed it to Pietro Urbani’s Selection of Scots Songs, harmonized and improved, and later reprinted it in James Johnson’s The Scots Musical Museum and also George Thomson’s Select Collection of Scottish Airs. Through such publications, the oral tradition of Scotland was being established in print and made palatable for drawing-room performances in polite society:

Song: ‘O, my luve’s like a red, red rose’

O, my luve’s like a red, red rose,

That’s newly sprung in June:

O, my luve’s like the melodie,

That’s sweetly play’d in tune.

As fair art thou, my bonnie lass,

So deep in luve am I:

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

’Till a’ the seas gang dry. go dry

’Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi’ the sun:

I will luve thee still, my dear,

While the sands o’ life shall run.

And fare thee weel, my only luve!

And fare thee weel a-while!

And I will come again, my luve,

Tho’ it were ten thousand mile!

Some of Burns’ own compositions, however, were more personal in origin. As noted above, while staying in Edinburgh in 1787-8, he met a married woman, Agnes or ‘Nancy’ McLehose, with whom he conducted a brief, intensely passionate correspondence, each taking the role of a neo-classical lover, ‘Sylvander’ and ‘Clarinda’. The surviving letters are testaments to an intense relationship that is also self-conscious and self-dramatising, on both sides. Nancy McLehose also aspired to be a poet, and Burns matched one of her songs (‘Talk not of love, it gives me pain’) to a traditional tune and submitted it to Johnson’s The Scots Musical Museum. The relationship cooled eventually, and McLehose returned to her husband, who was living in Jamaica, for a temporary reconciliation. Before Nancy’s departure, Burns copied this song into a letter to her:

Song: ‘Ae fond kiss, and then we sever’

Ae fond kiss, and then we sever;

Ae fareweel, and then for ever!

Deep in heart-wrung tears I’ll pledge thee,

Warring sighs and groans I’ll wage thee.

Who shall say that fortune grieves him

While the star of hope she leaves him?

Me, nae cheerfu’ twinkle lights me;

Dark despair around benights me.

I’ll ne’er blame my partial fancy,

Naething could resist my Nancy;

But to see her, was to love her;

Love but her, and love for ever.—

Had we never lov’d sae kindly,

Had we never lov’d sae blindly,

Never met—or never parted,

We had ne’er been broken hearted.

Fare thee weel, thou first and fairest!

Fare thee weel, thou best and dearest!

Thine be ilka joy and treasure,

Peace, enjoyment, love, and pleasure!

Ae fond kiss, and then we sever;

Ae farewell, alas! for ever!

Deep in heart-wrung tears I’ll pledge thee,

Warring sighs and groans I’ll wage thee!

Burns, in his life and in his letters and songs – and indeed in all the poetry he composed – was a man who demonstrated a passionate engagement with many aspects of life, but who remains elusive. He was spiritual but mocked the institutions of the church; he espoused radical politics, and in particular the ideals of the French revolution, but he also developed a network of friends and protectors amongst the landed gentry of south-west Scotland; he avowed eternal love, even while moving on to the next woman, and the next. He can easily be considered fickle, even contradictory, but it is perhaps more in keeping with the spirit of the age to see him enacting a multi-faceted personality by performing roles and adopting stances that he was wholly committed to – while they lasted.

After his early death, from rheumatic fever, his celebrity only increased. Statues of Burns, for example, pepper not only Scottish towns and parks, but they are evident in America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Nevertheless, the scholar Suzanne Gilbert questions the continuing practice of memorialising ‘Scotland’s national poet’ in stone, observing:

Making a monument of Burns does him disservice. A monument is stationary, acted upon rather than acting, whereas Burns’s poetry, above all else, celebrates active living.

The poetry and song of Burns, then, are the literary climax of a century that, if nothing else, celebrated active living through its arts. The 18th century saw the first poets and songwriters making an active choice to use Scots in their work – against the grain of increasing literacy in English throughout the new polity of Great Britain. These writers drew on the oral resources of song and ballad, disseminated their work through live performance, broadside and books, and integrated the energy of folk culture with the literate culture they found in a variety of forms, from classical translation to Enlightenment philosophy.

At the start of the century, they affected a Horatian ideal of civilised distance from the vices of the metropolis; Burns could still benefit from embodying the apparently ideal synthesis of ploughman and poet. But Burns died, on the precipice of debt, in his late thirties, having made no substantial profit from his literary fame. The notion of a professional literary artist was still to be developed. The next century would change all that.

Further reading and links

Brown, R. (2012). Robert Fergusson and the Scottish Periodical Press. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Carruthers, G. (2009). The Edinburgh Companion to Robert Burns. Edinburgh University Press.

Crawford, R. (2010). The bard: Robert Burns, a biography. Random House.

Gilbert, Suzanne (1998) “Recovering Burns’s Lyric Legacy: Teaching Burns in American Universities,”Studies in Scottish Literature, 30(1), 137-145

Leask, N. (2010). Robert Burns and Pastoral: Poetry and Improvement in Late-18th Century Scotland. Oxford University Press.

McGuirk, C. (1981). Augustan Influences on Allan Ramsay. Studies in Scottish Literature, 16(1), 97-109.

The broadside version of Allan Ramsay’s ‘Lucky Spence’s Last Advice’ can be viewed at http://digital.nls.uk/broadsides/broadside.cfm/id/15904

A digital facsimile of Robert Burns’ ‘Kilmarnock Edition’ is available at http://www.scottishcorpus.ac.uk/cmsw/burns/

Many websites are dedicated to Robert Burns and his work. Two of the most interesting places to start are http://www.burnsmuseum.org.uk/ and http://www.burnscotland.com