The previous chapters suggest ways in which the success of Sir Walter Scott’s historical romances opened a space for authors to write novels showing the interaction between individual agents and the kind of historical processes that intrigued the philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment. For example, John Galt’s The Annals of the Parish explores the ways in which self-interest, changing technology, and the rise of an industrial economy and global trade contribute to the broader historical transformations that were implicated in the move from a society founded on agriculture to one that is based on commerce.

In the late 18th and early 19th century, the market for literary and non-literary prose boomed, and Edinburgh consolidated its position as a publishing centre. Another great achievement of the Scottish Enlightenment was the Encyclopædia Britannica, first published between 1768 and 1771. The thirst for knowledge was such that by its fourth edition (published in 1810) it had grown to 40 volumes, including an entry on ‘Chivalry’ by Walter Scott.

Older and perhaps less respectable fictional genres, however, did not entirely disappear as the age of reason unfolded. In particular, the taste for Gothic romances – for tales of terror and the supernatural – found eager readers who were well-provided for by the novels and magazines of the period.

Monthly magazines founded in Scotland’s capital city flourished on a diet of fact, fiction, poetry and reviews: the Edinburgh Review was relaunched in 1802, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine was founded in 1817, and Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal followed in 1832. The Edinburgh Review and Blackwood’s were distinguished by their political affiliations, the former favouring the Liberal or Whig party, which by the 19th century was becoming associated with the interests of commerce and the supremacy of parliament over the crown. Blackwood’s was founded in part as a mouthpiece for opposing Tory views, which can be broadly characterised as an enthusiastic loyalty to the monarchy and support for the landed gentry against the up and coming merchant classes.

Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, or ‘Maga’ as it was affectionately known to its contributors and readers, was a major cultural force throughout the 19th century, publishing authors like John Galt, James Hogg, Margaret Oliphant, Arthur Conan Doyle and, looking beyond Scotland, George Eliot, Anthony Trollope and Joseph Conrad. It became particularly associated with ghost stories, and the developing genre of Gothic fiction.

It is tempting to read Gothic as the dark side of the Enlightenment. If the Enlightenment philosophers sought rational causes for the rise of civilisation, and Galt gently satirized Micah Balwhidder’s interpretation of inevitable historical changes as evidence of divine ‘Providence’, Gothic writers stubbornly insisted the power of the supernatural. The roots of Gothic in the English novel can be seen in the fiction of Horace Walpole, especially The Castle of Otranto (1764), Anne Radcliffe, Mysteries of Udolpho (1794) and Matthew Lewis, The Monk (1796).

In these novels, general themes are recycled: an exotic location, often in Catholic Europe; eerie night-time episodes of terror in mediaeval ruins; and threats to female virtue, often at the hands of warped aristocrats or perverted clergymen. Walter Scott goes so far as to directly refer to these works in his introduction to Waverley, mainly in order to distance himself from the excesses of the genre, while acknowledging its popularity:

Had I, for example, announced in my frontispiece, ‘Waverley, a Tale of other Days,’ must not every novel-reader have anticipated a castle scarce less than that of Udolpho, of which the eastern wing had long been uninhabited, and the keys either lost, or consigned to the care of some aged butler or housekeeper, whose trembling steps, about the middle of the second volume, were doomed to guide the hero, or heroine, to the ruinous precincts?

‘Every novel-reader’ in 1814, according to Scott, would have been familiar with the conventions of Gothic, and, though they might disparage it, they would have had a copy of Walpole or Lewis on their bedside table, and they would have succumbed easily to their guilty pleasures. At the outset of his career as a novelist, Scott is here insisting that the pleasures of Waverley are of another order.

And yet the reading public continued to gobble up tales of terror. Their lasting popularity raises the question of how we are to read Gothic novels and stories. One obvious response is to argue that if novels like The Annals of the Parish offer a fictional analysis of society, then tales of the supernatural offer a fictional analysis of the psyche. They tell us how civilised man and woman in the 19th century imagined and dealt with their internal demons.

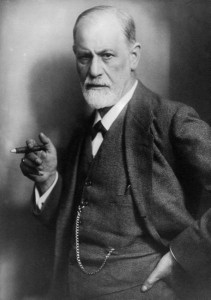

Modern readers of Gothic fiction who wish to relate it to psychic discontents can, of course, draw upon Freudian theories of the unconscious mind, which were formulated later in the 19th century. According to Freud’s Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis (First Lecture), in the process of maturing from infancy to adulthood, the individual goes through a process of repressing a set of animal, instinctive desires. The repression of these desires is necessary if individuals are to congregate in civilised social groups:

[…] we believe that civilization is to a large extent being constantly created anew, since each individual who makes a fresh entry into human society repeats this sacrifice of instinctual satisfaction for the benefit of the whole community. (15.23).

Chief amongst these repressed desires was the sexual impulse, which had to be sublimated so that the individual could achieve higher social goals. However, Freud suggested, these instincts were often so powerful that the repressed desires ‘returned’ in various forms; for example, breaking through to consciousness in the form of slips of the tongue and hallucinations or visions.

In a nutshell, Freudian theory offers a template for reading Gothic fiction as psycho-drama, on the following grounds: (i) fiction shares with the Unconscious a symbolic organisation; and ‘civilisation’ demands the repression of the individual’s unconscious instinctive desires, often sexual desires; (ii) ‘maturity’ involves a separation from animal instincts and a recognition of the ‘other’; (iii) in everyday life, these instinctive desires ‘return’ in the form of dreams, slips of the tongue, etc., (iv) in fiction, these desires ‘return’ in the form of fantasy, the grotesque, ghosts and demons. These assumptions invite us to ask the following questions of any Gothic tale:

- What is the nature of the supernatural or terrifying being?

- What is its relationship to the protagonist(s)?

- How does the manifestation of the supernatural or terrifying being relate to standard psychological themes, e.g.

- the formation of sexuality

- the ‘othering’ of the primitive/animal

- reality versus dreams?

With these questions in mind, we turn to four illustrative examples from Scottish fiction spanning the 19th century: James Hogg’s novel, The Private Memoir’s and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824); two pieces by Robert Louis Stevenson, the short story ‘Thrawn Janet’ (1881) and the novella, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886); and Margaret Oliphant’s short story, published in Blackwood’s, ‘The Library Window’ (1896).

James Hogg (1770-1835) was a contemporary of Scott and Galt, and, like Burns, came from a farming background. Hogg was born and raised in the rural Scottish Borders – indeed, he was nicknamed ‘The Ettrick Shepherd.’ Apparently stimulated by the example of Burns, Hogg began collecting ballads, and then writing poetry and novels, and, ten years after the publication of Scott’s Waverley, he published The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, satirising the same brand of religious extremism that Burns had memorably skewered in ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’.

Set in the 17th century, Hogg’s novel is one of the first fully-realised treatments of the theme of psychic dualism that would henceforth run as a continuous thread through the Scottish literary tradition. The story of the novel is, in fact, told twice, first, in the third person, by an ‘Editor’, and secondly, in the first person, by the ‘Justified Sinner’, a character named Robert Wringhim.

Both narratives tell Wringhim’s life story from different, incomplete and unreliable points of view: he was ostensibly born to a dissolute father and a devout mother, though there are strong hints that his true father is his mother’s religious adviser. This adviser is a Presbyterian minister who believes in the doctrine of Justification by Faith, described briefly in Chapter 6 in relation to ‘Holy Willie’s Prayer’.

In short, Robert is inducted by the minister into the belief that he is numbered amongst God’s elect; like ‘Holy Willie’, he believes that his salvation has been pre-determined, and so no act of his on earth can prevent his being accepted into heaven once he dies. Once Robert is convinced of his salvation, he begins to stalk his brother (or half-brother), George – and apparently Robert murders George in a tavern brawl. Robert disappears before his arrest.

The main difference between the ‘Editor’’s narrative and that of Robert himself is that the latter tells of a meeting with a mysterious stranger, Gil-Martin, which takes place shortly after Robert becomes convinced of his salvation. According to Robert it is Gil-Martin who encourages him to stalk his brother, and as the narrative continues, it seems that Gil-Martin has the ability to shift appearance, taking on Robert’s form to commit crimes, perhaps even the murder of George. As Robert’s narrative ends, it becomes clear that he now believes that Gil-Martin is the devil, he accepts he has been duped into believing that he was a member of the elect, and he plans to commit suicide, convinced of his own damnation. The ‘memoir’ is found in his grave.

Like many Gothic novels, Hogg’s fiction was presented as an authentic document. It was published anonymously, but Hogg is mentioned by name in the novel, almost as if to authenticate its veracity. Indeed, before the novel was published, Hogg printed a letter in Blackwood’s advertising the discovery of Wringhim’s ‘confession’ in his grave. The unease generated by Gothic fiction is often partly founded on its factual appearance. It is also partly founded on the unreliability of the narratives, here mainly seen in relation to the character of Gil-Martin: is he a real character, is he really the devil, or is he a figment of Wringhim’s increasingly deranged imagination?

There are indications to support different readings. ‘Gil-Martin’ or ‘Martin’s servant is a name given to the devil in folklore (e.g. in Sir Thomas Urqhuart’s Rabelais the devil is referred to as ‘St Martin’s running footman’), and there are various suggestive conversations in which Gil-Martin seems to be acknowledging his satanic nature:

“I have no parents save one, whom I do not acknowledge; therefore pray drop that subject .”

On the other hand, Gil-Martin is at one point seen by a third character (a prostitute), but there are also hints towards the novel’s conclusion that Gil-Martin and Wringhim inhabit the same body, that they are in fact the same person.

Gil-Martin is the main supernatural or terrifying element in Hogg’s novel, and so we can legitimately ask questions about his nature, his relationship to the protagonist (Wringhim) and how he relates to standard psychoanalytical themes sketched briefly earlier. There are clear clues in the novel about sibling jealousy and forbidden sexual desires that Gil-Martin encourages Wringhim to indulge; Gil-Martin invites the return of Wringhim’s repressed animal instincts. More generally, Scott Brewster cites his fellow scholar, Ian Duncan, in support of the following argument:

As Ian Duncan points out, Hogg understood himself emerging from pre-modern, largely pre-literate rural folk culture, its authentic primitivism distinct from a politically aware rural working class of south-west Scotland associated with Burns. Hogg’s concern with delirium, paranoia and obsession expresses his critical engagement with post-Enlightenment modernity and with rural traditions, his sense of being inside and outside both of these temporalities. (Brewster, p. 80)

Gil-Martin represents madness in the age of reason, but also the return of the devil and demonic forces that have been repressed in a period that was increasingly associated with scepticism and science. As Brewster and Duncan observe, Hogg’s background as a rural farm-labourer turned Enlightenment poet and novelist situated him between worlds, the agricultural domain of belief and superstition, and the secular domain of the city. Robert Wringhim also perhaps symbolises a ‘fractured’, pre-Union psyche – his name recalls that of the exemplary Scottish monarch, Robert the Bruce, while that of his half-brother is George, the name customarily given to kings of the Hanoverian dynasty. The duality in Robert’s character – the struggle between the demonic forces of animal barbarity and those of enlightened civilisation – establishes a narrative pattern that endured well into the following century.

One writer very obviously influenced by Hogg’s Gothic narrative is Robert Louis Stevenson. Two pieces of fiction that show his influence are the story, ‘Thrawn Janet’ and the novella, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. Stevenson was born in 1850, 15 years after the death of Hogg, into a strictly religious, middle-class Edinburgh family of lighthouse engineers. This was to be Stevenson’s vocation, but he was a sickly child and adult, and in 1871 he gave up the study of engineering to pursue a life of literature, much against his family’s wishes.

In 1873, on a trip to London, he met Sidney Colvin, a critic who had connections with Cornhill Magazine, and Colvin became Stevenson’s literary adviser. Stevenson began writing essays on various topics, including his travels. He journeyed to France, shortly after meeting Colvin, in order to recuperate from an illness, and he began to frequent artists’ colonies there. During a visit, three years later, he met Fanny Osborne, an American who was married, but separated, and who had three children. They fell in love, and, once more against his parents’ wishes, they married in California in 1880. They continued travelling throughout their marriage, traversing Europe and North America, and the family eventually ended up in Samoa, where they made their final home. Stevenson continued to write essays and travelogues, but he was also gaining a reputation for fiction, especially short stories, often with a Gothic element. ‘Thrawn Janet’, which was published in Cornhill Magazine in 1881, belongs to this category.

The story is remarkable partly for being written largely in Scots. An introduction in English frames a first-person narrative that tells of a Presbyterian minister, Mr Soulis, who apparently witnesses the reanimation of a dead woman, ‘thrawn’ (or ‘stubborn’) Janet. Beatrix Hesse, in a study of German translations of this story, notes that many translators drop the English introduction and tell the first-person narrative using standard language. This, she points out, dissipates much of the tension that the frame story contributes.

There are marked contrasts between the English introduction, which is located in the 18th century, elegantly phrased in literate, written language, and represents enlightened rationalism, and the first-person Scots narrative, which represents orality, is set in the late 17th century, and represents credulous superstition. In these respects, the two constituents of the story recall the Editor’s narrative and the first-person narrative of The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. In Stevenson’s story, however, the narrator is not Mr Soulis himself, but a local villager, who has little time for the scholarly minister’s passion of learning:

“ […] and there were folk even then that said the Lord had left the college professors to their ain devices, an’ the lads that went to study wi’ them wad hae done mair and better sittin’ in a peat-bog, like their forebears of the persecution, wi’ a Bible under their oxter and a speerit o’ prayer in their heart. There was nae doubt, onyway, but that Mr. Soulis had been ower-lang at the college.”

As in Hogg’s narrative, as Hesse observes, the unease that comes from Gothic fiction often derives from not knowing the degree of reliability that the narrator can command. If the narrator is reliable, then the devil is real and the dead can walk; if the narrator is unreliable then, as readers, we realise with a dreadful thrill that we are in the company of a madman.

Stevenson became increasingly successful as a novelist: his first popular novel was Treasure Island (1883), his children’s novel of pirates and buried treasure. He followed this with Kidnapped (1886), another coming-of-age story, reminiscent of Walter Scott’s Waverley novels in its historical setting, its strong characters, and the thematic structure, which sees a Scottish lowlander travel through the Highlands, have adventures and fall in love. It is Stevenson’s third novel that returns to the Gothic themes of his short stories, and to the trope of unreliable narration – and on the publication of Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), he enjoyed international fame as a literary celebrity.

Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a further expression of the theme of duality that surfaced in Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, but its sources are manifold. Stevenson was probably partly inspired by the urban legends surrounding the historical character of Deacon William Brodie (1741-88), who had been a respectable cabinet-maker and Edinburgh town councillor by day and a secret gambler and burglar by night. Brodie was popularly believed to have been hanged on a gallows of his own making.

Stevenson probably also read in Cornhill Magazine early accounts of ‘multiple personalities’ in articles translated from French. These essays on ‘the double brain’ were early attempts to understand this psychological condition. And, by his own account, or at least by Fanny Stevenson’s later report, the germ of Stevenson’s idea for the novella came to him – appropriately – in a nightmare.

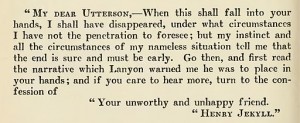

The ten short chapters of the novella take the concept of the unreliable narrator to a new height by offering a whole sequence of stories and storytellers: there is a third-person narrator, but there are also first-person accounts of events by characters in the novel, including Mr Enfield, Dr Lanyon, a maid, and Henry Jekyll’s own ‘private memoir and confession’ which makes up the final chapter. Since few of these characters is entirely trustworthy, or in some cases entirely sane, the reader is frequently invited to re-interpret the novel in his or her own way.

And so the story has been subjected to a number of retellings. Furthermore, the sequence of incidents told by these narrators does not follow the order of events in time: not until the penultimate chapter do we read a witness’s account of the transformation (of Hyde into Jekyll, not Jekyll into Hyde, as in most film versions), and not until the final chapter do we read Jekyll’s full account of the experiments that led to the unleashing of his darker self. The reworking of the chronological sequence defers the pleasure of knowing – the climax comes as a series of letters presented to the lawyer, Utterson, that he is instructed to read in a particular sequence, modelling the reader’s tortuous journey through the narrative.

One example of the ‘openness’ of the novel to reinterpretation comes in the fourth chapter, which recounts Hyde’s murder of a politician, Danvers Carew, from the perspective of a maid, the only witness. We are told that she is romantically inclined and almost asleep when she sees the two men encounter each other, late at night. She remarks that the older man is ‘beautiful’ and that his manners are ‘pretty’ when he ‘accosts’ the younger man and points his cane, apparently seeking direction; however, she cannot account for the ferocity of Hyde’s sudden attack on him.

A reader who is inclined to be less romantic than the maid might pick up on several apparent clues and reinterpret the older man’s conversation as a sexual advance that Hyde violently rejects, and much of the recent literature on Jekyll and Hyde reflects on the possibilities of reading the novella psychoanalytically, as an expression of repressed homosexual desire and panic. Most of the characters are middle-aged, unmarried professional men; there is no female romantic interest in the story. The ‘supernatural’ or ‘terrifying’ aspect of the novel is Hyde. He resembles Gil-Martin in that his appearance is difficult for the other characters to describe: he is younger than Jekyll (Utterson and Enfield believe that he has grounds to blackmail Jekyll, but the reasons are left open to speculation), he is physically active, and he is described by Jekyll as ‘ape-like’. He can be seen easily as a form of repressed, animal-like, instinctive Other, the return of a form of repression which may have a sexual association for these single, respectable, middle-aged men.

On the other hand, Hyde has also been read as a form of ethnic or cultural repression: the few descriptions of him in the novel have been likened to stereotypical descriptions of Irish or Highland criminals in the press of the time. Hyde may be the return of the Celtic other.

Its very genre-blending hybridity – from Gothic horror to medical narrative – adds to the power of Stevenson’s slim novel. It owes much to Hogg, and no doubt also to Stevenson’s upbringing in an Edinburgh that had a respectable and an unrespectable side to it. But in one respect it is different from The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner and even ‘Thrawn Janet’. Although Stevenson still insists that the irrational, and the fantastic lurks just underneath rational, civilised society, the source of that fantastic horror is no longer the superstitious past – it is modernity. It is Dr Jekyll’s laboratory experiments that unleash the monster; the secular processes of science and progress have replaced demonic possession as the means by which the repressed Other returns.

A fear of modernity also permeates our final Gothic chiller, Margaret Oliphant’s ghost story, ‘The Library Window’. Oliphant (1828-1897) was a considerable figure in 19th century Scottish literature: she published her first novel, Passages in the Life of Mrs Margaret Maitland, in 1849, and two years later, she met the editor, William Blackwood, which led to a long association with Blackwood’s Magazine, both as an author and literary critic. Oliphant had a difficult life: her husband died in 1859, leaving her to support their three children through her writing. Her brother also encountered financial difficulties and she had to support his family too. All her children predeceased her; she died, still professionally active, at the age of 69.

The ghost story, ‘The Library Window’ was published towards in 1896, towards the end of Oliphant’s life. In the story, a young girl, surrounded by chattering women, looks out of the window at the library opposite, and sees, framed in the opposite window, a young man, reading. She later discovers that the window is in fact an illusion; the space has been bricked up and the young man must have been a ghost. She also learns that, when he was alive, the young man had been attracted to and waved at one of her ancestors. The ancestor’s brothers found out about the sentimental attachment, and murdered him. The girl continues to see the ghost periodically; at one point in the narrative, he slams his window shut, and members of the crowd below look up.

How might we read this manifestation of the supernatural? One obvious answer is that the young man represents the girl’s repressed sexual yearnings, as (perhaps) Hyde represents Jekyll’s repressed sexual desire. We learn that the girl’s father is also a writer, so we might be tempted to relate the story to Jungian theories of the Electra complex, in which the daughter competes with the mother for the attention of the father, represented here by the ghost. But Tamar Heller has suggested another way of reading this story – as a yearning for the repressed desire to write. The girl looking out of her window sees a male domain, a quiet space for study and writing. As she watches the young man engaged in the act of writing, she becomes almost sexually aroused:

It was like a fascination. I could not take my eyes from him and that little scarcely perceptible movement he made, turning his head. I trembled with impatience to see him turn the page, or perhaps throw down his finished sheet on the floor, as somebody looking into a window like me once saw Sir Walter do, sheet after sheet. I should have cried out if this Unknown had done that. I should not have been able to help myself, whoever had been present; and gradually I got into such a state of suspense waiting for it to be done that my head grew hot and my hands cold.

Heller points out that there is evidence that Oliphant, like the girl in her story, yearned for the impossible condition of being a male professional writer, like ‘Sir Walter’, here alluded to. In her Autobiography, Oliphant recalls:

[U]p to this date (1888), I have never been shut up in a separate room, or hedged off with any observances. My study, all the study I have ever attained to, is the little second drawing-room where all the (feminine) life of the house goes on; and I don’t think I have ever had two hours undisturbed (except at night, when everybody is in bed) in my whole literary life.

Elsewhere in her writings, Oliphant is, however, critical of the rise of the ‘new woman’, who was emerging even in the late 19th century as sexually more liberated and economically more independent of men than her predecessors. And so the projection of a young male, with the space and freedom to engage in study and authorship might have been a desire that Oliphant, like her heroine in the story, repressed. And if so, then, like Stevenson, the repressed here symbolises a frightening aspect of modernity: the rise of the female professional, or the ‘new woman’.

Gothic fiction, then, is as adaptable and potent a means of analysing psychological states and cultural change as is the more social-realist narratives of writers like John Galt. In the novels and stories mentioned, the supernatural or terrifying elements can all be interpreted – albeit flexibly – as the return of repressed elements of the psyche or of society.

In Hogg, and in Stevenson’s ‘Thrawn Janet’, the older, superstitious, folkloric elements of Scotland return to haunt the rational, sceptical Enlightenment. And in Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and ‘The Library Window’, scientific meddling and ghostly apparitions represent new fears – that progress will uncover forbidden desires and that the settled relationship between the sexes will be overturned.

Scottish Gothic fiction draws on a rich tradition of supernatural and grisly tales – from the magical ballads to urban legends of body snatchers and characters like Deacon Brodie. Some of the Gothic fiction we have considered in this chapter is ‘spectacularly’ Scottish – ‘Thrawn Janet’’s English-framed, oral narrative is, as we have seen, part of the essential contrast that Stevenson establishes between the rational Enlightenment and the unenlightened, superstitious past. But other stories, like Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde are less Scottish in their content: Stevenson’s novella is set in London and draws as much on French psychology as it does on James Hogg.

As the 19th century progresses, then, some Scottish literature becomes more cosmopolitan in nature – there was early evidence of this trend in those of Walter Scott’s novels with non-Scottish settings, like Ivanhoe, Quentin Durward and The Talisman. But some Scottish fiction continued to draw on its explicit ‘Scottishness’ as a resource – mainly through its use of Scots in the dialogue. As the century passed, these more obviously ‘realist’ Scottish novels began to become more formulaic and less challenging. Their continuing success – and their establishment of literary stereotypes that lasted well beyond the 19th century – is the subject of our final chapter.

Further reading and links

Brewster, Scott (2005). “Borderline experience: madness, mimicry and Scottish Gothic.” Gothic Studies 7, no. 1, 79-86.

Carruthers, Gerard (2001) Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, The Master of Ballantrae and The Ebb Tide. Glasgow: ASLS Scotnotes

Duncan, Ian and Douglas Mack, eds. (2012) The Edinburgh Companion to James Hogg. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Felluga, Dino (2011). “Modules on Freud: On the Unconscious.” Introductory Guide to Critical Theory. Purdue U. [Accessed May 3, 2013].

Fielding, Penny (2010). The Edinburgh Companion to Robert Louis Stevenson. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Heller, Tamar (1997). “Textual Seductions: Women’s Reading and Writing in Margaret Oliphant’s” The Library Window”.” Victorian Literature and Culture 25, 23-38.

Hesse, Beatrix (2010). “The unco tales of Robert Louis Stevenson in German Translation.” International Journal of Scottish Literature, 7.

Petrie, Elaine (1988) James Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. Glasgow: ASLS Scotnotes

There is a wealth of information about Robert Louis Stevenson at http://www.robert-louis-stevenson.org/ and a 2013 edition of the lively online Scottish literary magazine The Bottle Imp celebrated his artistry.

The works of James Hogg and Margaret Oliphant are available at their respective Project Gutenberg sites.