In the final chapter of this short survey of Scottish literature from 1500-1900, we consider the popular but critically reviled ‘kailyard’ school of writing that began to be identified towards the close of the 19th century, and the ways in which the representations of Scotland and its people hardened into a set of literary and visual stereotypes that would endure well into the following century – indeed many of the ‘typical’ features of Scottishness that kailyard celebrates are still evident in popular culture today.

The immediately preceding chapters touched on two general strains of Scottish fiction that emerged over the 19th century. The first was a largely realistic mode of writing, such as that of John Galt, which explored social and historical issues and changes, often in the context of particular small-town communities, in which extravagant or comic characters, usually associated with the peasantry or the older generation, were often distinguished by their Scots speech.

The second was a genre of Gothic fiction that remained popular but arguable became less distinctively ‘Scottish’ in its content and themes; although Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, for example, can be seen in the context of its author’s Scottish Calvinist upbringing, and in the light of its Scottish antecedents, it is set in the British capital, and addresses themes of psychic duality that are arguably of universal relevance.

It is perhaps not surprising, then, that as the 19th century progressed, ‘Scottish’ literature became more narrowly associated with the heirs of the realist mode of fiction, set in identifiably Scottish communities that were populated by characters, many of whom spoke a recognisable variety of Scots. These ‘kailyard’ or ‘cabbage-patch’ novels were, effectively, the heirs of the regional novel, and they generally offered sentimental and comforting stories of rural life for the entertainment of their readers. And they were extraordinarily popular, both within Scotland and beyond its borders.

As these novels were being written and voraciously consumed, however, the discipline of ‘English Literature’ was gradually forming in British universities, led, as Robert Crawford has argued, by academic developments in Scotland. Ironically, perhaps, as the discipline of ‘Eng Lit’ grew, in its earlier years, it was influenced by cultural commentators such as Matthew Arnold, whose book Culture and Anarchy (1869) argued that the literature worth studying needed to be of timeless, universal value. In a famous formulation of ‘high culture’, he proclaimed:

Culture […] is a study of perfection [… It] seeks to do away with classes; to make the best that has been thought and known in the world current everywhere; to make all men live in an atmosphere of sweetness and light […]”.

One of the results of the dissemination of setting this normative value was to marginalise those genres of fiction, poetry and drama that were distinctively regional, rather than universal. As Robin Gilmour (p. 57) puts it:

Arnold’s formulation of Culture as a transcendent value is a crucial development, because it drove a wedge between regionalism and culture, stigmatising the one as enfeebled provincialism, and raising the other above the claims of time and place.

Regional novels, moreover, might easily be accused of a lack of ambition, and an easy reliance on familiar formulae. This was recognised as early as 1889 by Margaret Oliphant, in a review in Blackwood’s Magazine (pp 265-6):

The books called “Carlowrie”, “Aldersyde”, “Blinkbonny,” “Glenairlie” &c are cheap books, perfectly well adapted, with their mild love stories and abundant marriages, for the simpler classes, especially of women whose visions are bounded by the parish, who know nothing higher in society than the minister and his wife, and believe that all the world lieth in wickedness except Scotland. […] It is sad to be told that these productions are regarded as representatives of a national school and attain their popularity by dint of their dialect and by the very narrowness of their aim.

The kailyard novelists best remembered now include Ian Maclaren (e.g. Beside the Bonnie Briar Bush), S.R. Crocket (e.g The Stickit Minister), and J. M. Barrie (e.g Auld Licht Idylls, A Window in Thrums). Their novels tend to be episodic, humorous descriptions of rural Scottish life, with, as Oliphant says, ‘mild love stories and abundant marriages.’ They were comforting reads, on the whole, celebrating the nostalgic values of a simple, rural existence: humility, modesty, decency, community, piety, poverty, and the kind of uneducated native ingenuity that the Scots call ‘canniness’. Familiar characters populate the pages: as well as the amusing peasantry, there are a set of professionals who function as mediators between the reader and the characters in the stories. Like the reader, these professionals – often a doctor, a minister, a lawyer or a ‘dominie’ (a teacher) – use standard English, and their narrative frames the dialogue of the Scots-speaking characters.

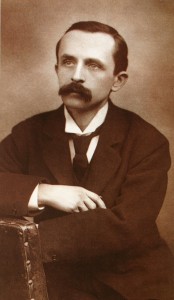

Perhaps the most interesting author of the kailyard school is J.M. Barrie. He was born in the north-east of Scotland, in the small town of Kirriemuir in Angus, in 1860, ten years after the birth of Stevenson. He developed an interest in storytelling in a childhood that was marred, when he was six years of age, by the death of his brother, David. When he grew up, Barrie attended Edinburgh University, and started working for an Edinburgh newspaper as a drama critic. His transition into novel-writing came through journalism, and his first novels, Auld Licht Idylls (1888), A Window in Thrums (1890), and The Little Minister (1891) are in the kailyard style, and are based on his youthful memories of Kirriemuir (which becomes the fictional setting of ‘Thrums’). The novels were an international success and Barrie moved to London, where he began to work on drama; his stage play Peter Pan was produced in 1904, and his lasting fame was assured.

Andrew Nash, who is one of several scholars who have recently reappraised the kailyard school of writing, draws attention to the deepening maturity of Barrie’s style, as he moves from kailyard novelist to acclaimed dramatist (Nash, p.71):

At this stage of his career [ie when writing A Window in Thrums], he uses the narrator to try and convince the reader of the realism and veracity of the story, and of Jess and her family and the emotions involved in it. As his fictional career progressed, however, he became more interested in the role of the narrator and in the act of creating illusions of reality. His later novels are characterised by an intense interest in the creative mind; with storytelling and illusory realities.

The status and uses of literature, indeed, are among the topics gently addressed in Chapter X of A Window in Thrums, in which the narrator touches on the reading habits and tastes of the small-town inhabitants:

Two Bibles, a volume of sermons by the learned Dr. Isaac Barrow, a few numbers of the Cheap Magazine, that had strayed from Dunfermline, and a “Pilgrim’s Progress,” were the works that lay conspicuous ben in the room. Hendry had also a copy of Burns, whom he always quoted in the complete poem, and a collection of legends in song and prose, that Leeby kept out of sight in a drawer.

The weight of my box of books was a subject Hendry was very willing to shake his head over, but he never showed any desire to take off the lid. Jess, however, was more curious; indeed, she would have been an omnivorous devourer of books had it not been for her conviction that reading was idling. Until I found her out she never allowed to me that Leeby brought her my books one at a time. Some of them were novels, and Jess took about ten minutes to each. She confessed that what she read was only the last chapter, owing to a consuming curiosity to know whether “she got him.”

Here we can see a representation of the staple reading matter of ‘ordinary’ rural Scots in the late 19th century – religious matter (the Bibles, sermons and a copy of Bunyan’s religious allegory), stray examples of the periodical press that flourished in the 19th century (the ‘Cheap’ magazine), and some Scottish texts (an edition of Burns’ poetry and some folklore, possibly kept out of sight since its pagan values might predate or contradict the Christian ones of the sermons and Bibles). The values of piety and modesty in a poor setting are economically sketched here, as is the limit to the peasantry’s desire for education or self-improvement. Like the narrator of ‘Thrawn Janet’, the villager, Hendry shakes a sceptical head at the ‘weight of my box of books’, and shows no inclination to read the contents. The woman, Jess, however, does read novels – still seen in conservative circles as an ‘idle’ female occupation – but only insofar as she skips to the last chapter to check the outcome of the familiar marriage plot.

A further concern with the social status of literary celebrity is evident in Chapter XVII, ‘A Home for Geniuses’, in which the English-writing narrator recounts a conversation with a Scots-speaking villager, Tammas. Tammas has an idea for the care and maintenance of native intellectuals:

From hints he had let drop at odd times I knew that Tammas Haggart had a scheme for geniuses, but not until the evening after Jamie’s arrival did I get it out of him. Hendry was with Jamie at the fishing, and it came about that Tammas and I had the pig-sty to ourselves.

“Of course,” he said, when we had got a grip of the subject, “I dount pretend as my ideas is to be followed withoot deeviation, but ondootedly something should be done for geniuses, them bein’ aboot the only class as we do naething for. Yet they’re fowk to be prood o’, an’ we shouldna let them overdo the thing, nor run into debt; na, na. There was Robbie Burns, noo, as real a genius as ever—”

At the pig-sty, where we liked to have more than one topic, we had frequently to tempt Tammas away from Burns.

“Your scheme,” I interposed, “is for living geniuses, of course?”

“Ay,” he said, thoughtfully, “them ‘at’s gone canna be brocht back. Weel, my idea is ‘at a Home should be built for geniuses at the public expense, whaur they could all live thegither, an be decently looked after. Na, no in London; that’s no my plan, but I would hae’t within an hour’s distance o’ London, say five mile frae the market-place, an’ standin’ in a bit garden, whaur the geniuses could walk aboot arm-in-arm, composin’ their minds.”

“You would have the grounds walled in, I suppose, so that the public could not intrude?”

“Weel, there’s a difficulty there, because, ye’ll observe, as the public would support the institootion, they would hae a kind o’ richt to look in. How-some-ever, I daur say we could arrange to fling the grounds open to the public once a week on condition ‘at they didna speak to the geniuses. I’m thinkin’ ‘at if there was a small chairge for admission the Home could be made self-supportin’. Losh! to think ‘at if there had been sic an institootion in his time a man micht hae sat on the bit dyke and watched Robbie Burns danderin’ roond the—”

The main purpose of kailyard fiction is to elicit sympathy and respect for the simple but honest response of villagers to the complexities of modern life. At worst, the narrator and reader become complicit in a stance of condescension towards the rural folk depicted; at best they jointly assume an air of wistful nostalgia.

The degree to which Barrie and his kailyard counterparts succeeded in eliciting affectionate sympathy for rural Scottish life can be seen in the ecstatic reception Barrie received on a tour of the eastern USA in early 1897. The adulation he received caused a more sceptical Life magazine contributor to satirise him and the genre he represented in an article entitled ‘Donald MacSlushey in Boston’ (January 14th issue). Accompanied by two cartoons in which unintelligible Scots phrases are spelled out in banners and by fireworks (‘Ma wee wee galoot!’), the anonymous author presents ‘MacSlushey’ (ie Barrie) addressing a packed Music Hall in the New England capital:

His subject, “The All-Round Superiority of Scotland,” electrified the biggest audience of modern times. In the course of his remarks he said:

“And why is Scotland so far ahead of all the rest of Christendom? She has never produced a great painter, sculptor or musician. Her climate is cold and damp, while the salient features of her national costume are a scanty skirt and naked knees. Her music is the bagpipe! Her language, if you can call it such, is the harshest that ever shattered the tympanum of man. Yet, why, why, altho’ America, for instance, is swamped beneath a tidal wave of Scotch – of Scotch authors, Scotch literature and dialect – why is it, I ask, that we never tire of it?”

At this point a voice from the rear of the hall answered:

“But we do.”

The words were no sooner uttered, however, than furious women threw themselves upon the brute and tore him into fragments.

The Life article is testimony both to the fashion for ‘Scotch authors’ like Barrie at the end of the 19th century, and to the ‘anti-kailyard’ voices that were arising. It is significant that the most ardent fans of kailyard in Boston are represented as ‘furious women’ while the dissenting voice from the back of the hall is male.

Kailyard attitudes continued to dominate Scottish literary culture into the early part of the 20th century, not only in fiction but in the innumerable post-Burnsian volumes of poetry that also populated the bookshelves. Since the conversion of Walter Scott from popular poet to best-selling novelist, poetry had been overshadowed by the explosion of mass-market fiction; however, verse still found its eager audience, though a comparatively smaller one.

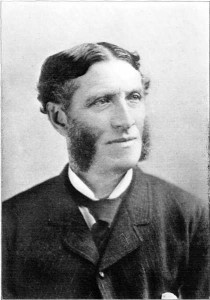

In some cases, like that of the versifying minister, J. Logie Robertson (1846-1922), the poems were originally published in newspapers before being collected in volumes. Robertson wrote under the pen name ‘Hugh Haliburton’, and his updated versions of Horace’s Odes and his own compositions both cast a backward-looking, nostalgic eye on Scottish culture. This attitude is perhaps most evident in ‘On the Decadence of the Scots Language, Manners and Customs’ from the posthumously published edition of Horace in Homespun (1925):

They’re wearin’ by, the guid auld times

O’ Scottish rants and hamet rhymes,

In ilka biggin’ said or sung

In the familiar mither tongue

When lads and lasses were convenin’

Roun’ the wide ingle at the e’enin’.

They’re wearin’ by, the guid auld days

O’ simple faith an’ honest phrase

Atween the maister an’ the man

In ilka corner o’ the lan’

When faithfu’ service was a pleasour,

An’ faithfu’ servants were a treasour.

[…]

Gude keep my Southlan’ freen’s fra’ hearin’

A rouch red-headed Scotsman swearin’

But wha would hae audacity

To question its capacity?

The mither croon’d by cradle side,

Young Jockie woo’d his blushin’ bride,

The bargain at the fair was driven,

The solemn prayer was wing’d to heaven.

The deein’ faither made his will,

In gude braid Scots

– A language still!

The excerpts from this poem recall an idealised Scotland as a rural idyll where kailyard values (honesty, piety, community) were assured: the community gathered to sing and tell stories, nobody questioned issues of faith or social hierarchy, family roles were constantly reiterated, the locus of the community was market and church, and the language of the community was broad Scots.

The reality for most Scots, as Robertson’s poem acknowledges in tones of nostalgic regret, was very different at the turn of the 20th century. The industrial revolution and the drift to the cities of Glasgow, Aberdeen, Dundee and Edinburgh meant that most Scots lived in urban conditions far removed from the rural idyll described by the kailyard novelists and poets. Many Scots, moreover, failed to find rural life in Scotland quite the pastoral paradise that it was conventionally portrayed to be. To a certain extent, as scholars like William Donaldson and Tom Leonard have argued, these dissenting voices were read in the radical fiction, essays and poetry that was published in newspapers of the period. This ‘hidden literature’ occasionally found its way into book form, but often remained outside the canon. And so – as Margaret Oliphant had prophesied – the kailyard authors and poets became representative in the broader public’s mind of ‘a national school’.

That school remained influential in popular culture well into the 20th century. Kailyard conventions can be seen – to give one example – in Country Doctor, a book published in 1934 by the Scottish novelist and physician, A.J. Cronin. This episodic story of a young doctor in a rural Scottish town in the 1920s became the basis for a popular BBC television series, Dr Finlay’s Casebook, which ran from 1962 to 1971.

The character was revived in a Scottish Television series, Dr Finlay, which updated the setting to the 1940s, but retained the kailyard formula of having the values of a professional male interact with those of quaint Scottish villagers. The formula was, indeed, exported – the US television series Northern Exposure which ran on CBS from 1990-1995 similarly involved a physician in a rural community, this time a New Yorker who goes to practise medicine in Alaska and finds his urban values clashing with those of the quirky, small-town community.

As kailyard moved from page, to stage, to television and film screens, the visual stereotypes that represented Scottishness merged. We have seen that the popularity of Walter Scott’s fiction led to a fashion for tartanry that has lasted to the present day, and kailyard and tartanry can be seen as mutually reinforcing stereotypes of Scottishness. Since the Waverley novels, tartanry has been associated with highland ancestry, sentimental Jacobitism, patriotic Scottishness and doomed romanticism.

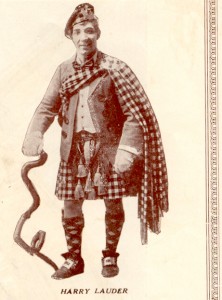

At the turn of the 20th century, the music-hall performer, Sir Harry Lauder (1870-1950), drew on stereotypes of both kailyard and tartanry. Despite coming from a lowland mining background, Lauder performed has act in full highland outfit, singing songs that celebrated kailyard values, and created a tight-fisted comic character who lived long in the popular imagination.

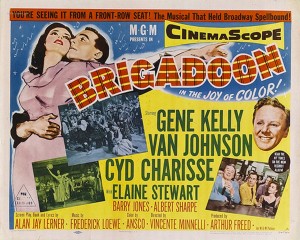

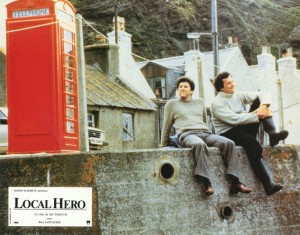

Perhaps the most interesting 20th century depictions of kailyard and tartanry on-screen are dramatisations of the interaction between small-town values and those of modernity. In two Hollywood productions – Brigadoon (1954) and Local Hero (1983) – modern American males encounter mythical small-town Scottish idylls, and are generally seduced by kailyard values.

In the American musical, shot entirely in Hollywood, the main characters, played by Gene Kelly and Van Johnson, are two tourists who discover a Scottish village, cursed only to appear once every hundred years. The character played by Kelly predictably falls in love with a local girl, and must make the decision either to return to the USA and modernity, or stay in Scotland, and the past.

A similar choice faces the character played by Peter Riegert in Local Hero. He plays a representative of an oil business who descends on a small Scottish town, hoping to convince the inhabitants to sell their land so that his company can build a refinery there. Written and directed by a Scot, Bill Forsyth, Local Hero both raises and undermines the kailyard stereotypes: the local villagers are only too happy to sell their land, but an obstacle arises in the character of ‘Old Ben’, who is the heir to the beach that he lives on and combs for flotsam that he can use or trade. From Old Ben, the more materialistic characters learn to reappraise their values – and the film ends with Riegert’s character returning to modern, materialist Texas, but nostalgic for the people and values of the small town he has left behind.

In both Local Hero and Brigadoon, Scotland functions as a site of magical transformation, a mythical or semi-mythical place where the stresses of modern materialism can be dissolved and individuals can be reconnected with more traditional, community values.

By the end of the 19th century, then, Scottish kailyard fiction had established a set of critically derided but nevertheless enduring tropes, or stereotypes. They represented Scotland as a place where a particular set of attractive, if conservative values were cherished and sustained – values that ran counter to the increasing secular materialism of urban society. In the twentieth century, many works of popular culture would draw upon these stereotypes, reshaping them for different audiences in different places and times.

There would, of course, continue to be dissenting voices, writers who challenged the ethos and aesthetics of kailyard and tartanry. In the early years of the 20th century, there would be a ‘modern renaissance’ of poetry in Scots, English and Gaelic that would challenge the literary establishment and seek to drag the nation into a new age. As the century progressed, novelists would experiment with new forms and revisit the past in critical and challenging ways. Later in the century, younger Scottish writers would enthusiastically adopt styles and values from an international avant garde, and some would gleefully take a blunderbuss to many of Scotland’s sacred cows.

Towards the end of the century, poets, novelists and dramatists alike would engage directly in the political movement to re-establish a degree of political autonomy to the Scottish nation, by supporting the case for a devolved Scottish parliament. But these stories are built on the foundation of the earlier centuries of Scottish writing, the centuries covered in this brief introduction.

Further reading and links

Crawford, R. (Ed.). (1998). The Scottish Invention of English Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gilmour, R. (1989). ‘Regional and Provincial in Victorian Literature.’ in The Literature of Region and Nation ed. RP Draper, Basingstoke: Macmillan, pp. 51-60.

Nash, A. (2007.) Kailyard and Scottish Literature. Amsterdam: Rodopi

Oliphant, M. (1889). “The Old Saloon” in Blackwood’s Magazine, August, pp. 265-6

Works by and about J.M. Barrie, including A Window in Thrums, can be located at his Project Gutenberg page, and at http://www.jmbarrie.co.uk/