As we saw in the last chapter, during the period between the death of James V in 1542, and the performances of A Satire of the Three Estates in 1552 and 1554, there was political and religious turmoil in Scotland – conflict reflected in the turbulent action of the play. While Lyndsay’s drama ends on a tentatively optimistic note of legal and religious reform, the crisis in Scottish public affairs was in fact intensifying.

At the time of the final performance of the play in 1554, James V’s widow, Mary of Guise, was acting as Queen Regent, and her daughter, also called Mary, was being raised as a Catholic in France – however, their Catholicism was coming under severe threat. For many years, Scottish clergymen, influenced by the reforming ideals of Martin Luther and John Calvin, had been building support amongst those Scottish landowners who were similarly disaffected with the Catholic Church.

They were encouraged by the Reformation south of the border, in 1535, during which Henry VIII had placed himself at the head of a new religious institution, the Church of England. The early-to-mid 16th century, then, saw violence spreading, as Scottish Protestant preachers were executed and a Catholic bishop murdered in retribution. In 1558, the young Mary married Francis, the French crown prince, or Dauphin, raising fears amongst the Reformers of a strengthened Catholic monarchy in Scotland. On the other hand, in the same year, a Protestant queen, Elizabeth I, acceded to the throne of England.

In 1560, Mary of Guise died, and the Protestant nobility negotiated a treaty with her daughter, now Mary, Queen of Scots, and her young husband, himself recently crowned King Francis II of France, to allow the Scottish lords the right to summon parliament. Once they did so, the Catholic Church was abolished and Scotland became a Protestant state.

Francis II died at the end of 1560, at the age of 16. Mary returned to Scotland, a widow, in 1561, opposed to the Protestant rulers. By this time, the main Protestant activist in Scotland was the clergyman, John Knox, and he denounced the young Catholic queen from the pulpit. Mary remarried, bore a son, James, in whose favour she was soon forced to abdicate, fleeing Scotland for refuge with Elizabeth I, her first cousin, once removed. She lived in custody in England for 19 years, while Scotland descended into civil war. The Protestants overcame Mary’s supporters, and Elizabeth, finally wearying of having a focus for disaffected Catholic insurgency in her own kingdom, allowed her execution in 1587.

Mary’s son, James VI of Scotland, was 21 years old when his mother was executed. He had already been king of Scotland for 20 of those years, although he did not gain full personal control of the country until 1583, when he was around 17. He had been raised as a Protestant, and as a child he had been provided with strict but learned governors, one of them George Buchanan, a humanist whose literary and philosophical works, composed in Latin, were known throughout Europe.

When he came to the throne of Scotland, James was actively interested in literature, and keenly aware of its value as a means of expressing cultural, social and religious ideals. He was also interested in promoting the prestige of his court as a focus of literature in a distinctive Scots vernacular, while simultaneously associating that literature with contemporary poetry from Europe, particularly through translation.

We know this because, in 1584, James had a self-penned treatise printed, known as The Essayes of a Prentise in the Divine Art of Poesie, but more fully entitled, Ane Schort Treatise conteining some Reulis and Cautelis [ie strategems or cautions] to be observit and eschewit in Scottis poesie. In this short treatise, James offers a unique insight into the aesthetic and political values underpinning the production of courtly literature in Scotland at the end of the 16th century.

Courtly literature in Scots had survived the disruptions of conflict with England and the internal religious strife of the Reformation. In the latter part of the 16th century, the poems and songs of Alexander Scott are notable for their earthy expression of aspects of love in direct and simple Scots:

To luve unluvit it is ane pane;

For scho that is my soverane,

Sum wantoun man so he hes set hir

That I can get no lufe agane,

Bot brekis my hairt, and nocht the bettir.

[…]

Quhattane ane glaikit fule am I glaikit: foolish

To slay myself with malancoly,

Sen weill I ken I may nocht get hir?

Or quhat suld be the caus and quhy

To brek my hairt, and nocht the bettir?

My hairt, sen thow may nocht hir pleiss,

Adew, as gude lufe cumis as gaiss,

Go chuss ane udir and forȝet hir;

God gif him dolour and diseiss,

That brekis thair hairt and nocht the bettir.

Scott died just as James VI was coming into power on his own; the senior poet at court became Alexander Montgomerie, then in his thirties. He was the son of an Ayrshire landowner, the author of sonnets, songs, flytings, a long allegorical poem called The Cherrie and the Slae … and he was a Catholic in the largely Protestant Scottish court.

James VI, then, had a strong vernacular tradition to draw upon and maintain when he wrote The Reulis and Cautelis. There were many direct precedents for writing an essay of instruction on verse composition. Horace’s Ars Poetica (c 18 BC) was well known in the later mediaeval and renaissance periods and one influential aspect of Horatian aesthetics was that the compositions should be decorous, that is, form should be matched appropriately to content:

The subject matter of comedy does not wish to find expression in tragic verses. […] Let each genre keep to the appropriate place allotted to it.

More immediately, there was a rise in the 16th century of European literary essays challenging the supremacy of Latin as a literary vehicle and championing the vernacular. These poetic ‘defences’ can be read as the stirrings of literary nationalism; James was certainly influenced by Joachim du Bellay’s Defence and Illustration of the French Language (1549), a copy of which is listed in his library, and which he certainly used as the basis of his own literary theory.

Doubtless James was also aware of what was going on over the border in England, where George Gascoigne’s Certayne Notes of Instruction had been published in 1575. We know from James’ introduction to his own essay that he was concerned to make available a pamphlet that would guide fellow poetic ‘apprentices’ in developing a Scots vernacular literary tradition. He is thus careful to distinguish Scots verse from verse in English; however, he unhelpfully suggests that the differences between the two literary languages are matters that he need not define, as they will be apprehended simply by ‘experience´:

The uther cause [of writing this essay] is that for thame that hes writtin in it [i.e. about poetic composition] of late, there hes never ane of thame writtin in our language. For albeit sindrie hes written of it in English, quhilk is lykest to our language, yit we differ from thame in sindrie reulis of poesie, as ye will find be experience.

– From the Preface to Some Reulis and Cautelis.

The essay then goes on to cover basic principles of poetic form, accompanied by comments on aesthetic value and political prudence. The essay discusses, in chapters of varying degrees of brevity:

- James’ reasons for writing

- Poetic rhythm

- The quantity and length of syllables

- Appropriate vocabulary

- Figures of speech

- Repetition

- Originality

- The proper subjects for poetry/translation

- Rhyme schemes

The precepts of many of the chapters can be projected back towards the earlier tradition of the makars. James’ comments on choosing vocabulary that is appropriate to the content is Horatian in theme and it also accounts for the practice of much earlier poets like William Dunbar, for whom vocabulary is a sensitive marker of a high, low or plain style and subject matter:

Ye man also take heid to frame your wordis and sentencis according to the mater: as in flyting and invectives, your words be cuttit short and hurland over heuch. For thais quhilkis are cuttit short, I meane be sic wordis as thir,

Iis neir cair

for ‘I sall nevir cair,’ gif your subject were of love or tragedies, because in thame your words man be drawin lang, quhilkis in flyting man be short.

– From Chapter III

Here, James identifies the subject of low style verse (flytings and invectives) and high style (love or tragedies), and indicates the kind of vocabulary appropriate to the former (words that have been ‘cut short’ or abbreviated, like ‘Ise’ for ‘I shall’ and ‘neir’ for ‘never’) and those forms (the longer, unabbreviated forms) appropriate to the latter. Warming to this theme, he identifies, in very general terms, the kinds of vocabulary he associates with learned poetry, love poetry, tragic poetry and ‘rustic’ or comic poetry (ie ‘of landwart effairis’):

Ye man lykewayis tak heid, that ye waill your wordis according to the purpose: as in ane heich and learnit purpose to use hiech, pithie and learnit wordis.

Gif your purpose be of love: to use commoun language with some passionate wordis.

Gif your purpose be of tragicall materis: to use lamentable wordis, with some hiech, as ravisht in admiratioun.

Gif your purpose be of landwart effairis: to use corruptit and uplandis wordis.

– From Chapter III

Chapter III also includes one of the few points that James explicitly identifies as characteristic of Scottish poetry, a love of alliteration (‘literall verse’). This formal feature, he advises, should permeate all Scots poetry, but it should be particularly obvious in ‘flytings’, those invective-laden poems in which rival poets hurl abuse at each other:

Let all your verse be literall, sa far as may be, quhatsumever kynde they be of, but specially tumbling verse for flyting. By ‘literall’, I meane that the maist pairt of your lyne sall rynne upon a letter, as this tumbling lyne rynnis upon ‘f’.

Fetching fude for to feid it fast furth of the farie.

The influence of James’ concern with the formal musicality of the line, with alliteration and with appropriate poetic diction, can perhaps be seen most clearly in the work of one of his court poets, John Stewart of Baldynneis. Baldynneis wrote a fawning dedication to James VI as a preface to his own poetry, making it clear that his own verse will follow his monarch’s advice:

SIR, haifing red ȝour maiesteis maist prudent

Precepts in the deuyn art of poesie, I haif assayit my

Sempill spreit to becum ȝour hienes scholler; Not that

I am onnywais vorthie, Bot to gif vthers occasion (seing

My Inexpertnes) to publiss thair better leirnyng.

And indeed, Stewart of Baldynneis’ poetry can easily be mined for lines illustrating James’ ‘most prudent precepts in the deuyn art of poesie’ [most prudent precepts in the devine art of poetry]. A short extract from his translation of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso as Roland Furious gives a brief taste of his mannered but energetic style:

He sees ane christall revere douce distell

About the bordour of ane medow fair,

Quhair flouris fresche maist savouruslie did smell

And monie seimlie frondise trie preclair

Obumbrat all this situation rair.

Here there is a typical abundance of alliteration on the initial stressed syllables in many lines, while ‘obumbrat’ (shadowed) harks back to the aureate Latin neologisms that we saw peppering Dunbar’s high style poetry earlier in the century. But now, instead of honouring Latin as the golden language, Stewart, urged on by James, is adapting into Scots an epic poem of love, composed in another European vernacular language, contemporary Italian.

In the shortest chapter in the essay, Chapter V, James again indicates a formal poetic feature that we find in poets like Dunbar, namely parallelism. This he terms ‘repetition’:

It is also meit for the better decoratioun of the verse to use sumtyme the figure of repetitioun, as:

Quhylis joy rang,

Quhylis noy rang. etc.

Ye sie this word ‘quhylis’ is repetit heir. This forme of repetitioun, sometyme usit, decoris the verse very mekle. Yea, quhen it cummis to purpose, it will be cumly to repete sic a word aucht or nyne tymes in a verse.

James employs the decorative and ‘comely’ feature of repetition in his own poetry, as we can see here, an address to the month of May:

Haill, mirthfull May, the moneth full of joye!

Haill mother milde of hartsume herbes and floweres!

Haill fostrer faire of everie sporte and toye

And of Auroras dewis and summer showres!

Haill friend to Phoebus and his glancing [shining] houres!

Haill sister scheine [bright] to Nature breeding all…

However, James’ instructions to his fellow poets embraced more than the formal features of verse. Aware, no doubt, that the vernacular could be used in promoting religious and political factionalism – his mother, after all, had been deposed and was still in prison in England at the time he wrote his advice – he warned court poets away from writing on political subjects, except indirectly:

Ye man also be war of wryting anything of materis of common weill or uther sic grave sene subjectis (except metaphorically; of manifest truth opinly knawin; yit nochtwithstanding using it very seindil) because nocht onely ye essay nocht your awin inventioun, as I spak before, bot lykewayis they are to grave materis for a poet to mell in…

These are fascinating lines for several reasons. First, James gives two reasons for not raising ‘matters of the commonwealth’ in literature – such matters are ‘too grave’ or too serious a subject for poetry, but he also suggests that drawing upon political subjects constrains a writer’s own ingenuity, or ‘invention’. (He has earlier warned the novice poet off translation for similar reasons.) This suggests that the ingenuity of the writer is highly valued in James’ court, more so than the incisive treatment of politically sensitive subjects. But James curiously offers his writers an escape clause: they can write about sensitive topics if they do so only occasionally, and indirectly, through metaphor. He thus sketches out a manifesto for political allegory in the modern age.

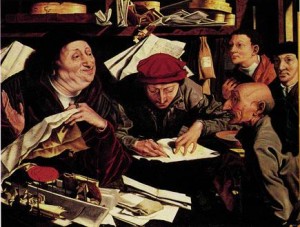

If John Stewart of Baldynneis is an example of someone using the young king’s essay as a template for his poetry, the older poet, Alexander Montgomerie, whose Catholicism made his position at court uneasy, found ways of negotiating a compromise between the king’s ‘prudent precepts’ and his own artistic and political expression. James VI quotes some of Montgomerie’s earlier poetry to illustrate his Reulis and Cautelis, but the following ‘flyting sonnet’ both challenges and conforms to the guidance the king has provided. It is a piece of fierce invective, a flyting, but in a form usually associated with love and celebration, a sonnet. It also refers obliquely to a real situation, and quite a sensitive one, in which Montgomerie felt betrayed by an ally, one of his own lawyers, whom he discovered was actually being employed by his enemy, Baxter. The situation revolved around a legal case in which Montgomerie was trying to reclaim his court pension from his rival, who had appropriated it in his absence. Montgomerie lost the case in 1593. The ‘flyting sonnet’ challenges notions of decorum, but it contains James’ preferred formal qualities of alliteration and repetition – like Dunbar’s earlier flyting, it is largely a list of insults:

A Baxters bird, a bluiter beggar borne,

Ane ill heud huirsone lyk a barkit hyde,

A saulles swinger, sevintie tymes mensworne,

A peltrie pultron poyson’d up with pryde,

A treuthles tongue that turnes with eviry tyde,

A double deillar with dissait indeud,

A luikar bak whare he was bund to byde,

A retrospicien whom the Lord outspeud,

A brybour baird that mekle baill hes breud

Ane hypocrit, ane ydill atheist als,

A skurvie skybell for to be escheu’d

A faithles, fekles, fingerles and fals,

A Turk that tint Tranent for the Tolbuith.

Quha reids this riddil he is sharp forsuith.

It is a curiously biting insult to denounce someone for being ‘fingerless’. The sonnet follows James’ advice to be indirect when dealing with political matters – here the final line announces that the poem is a riddle that can be solved if you are ‘sharp’. History tells us that the traitor, the false advocate who pretended to be Montgomerie’s ally, was called Sharp. In his poems of this time, Montgomerie frequently complained about his political mistreatment on religious grounds, flyting against his enemies and, eventually, even the king – and he was ultimately forced into exile and he died abroad.

James governed in Scotland until 1603, patronising a number of poets, including William Fowler, who translated Petrarch, and Alexander Hume, who wrote a number of religious poems, and a languid description of a surprisingly beautiful Scottish summer’s day ‘Of the Day Estivall’. The degree to which there was an active court culture in the sense of a band of poets, who met and promoted Scottish poetry at the time, is disputed – however, James VI was clearly interested in acquiring the cultural capital associated by developing a vernacular poetic tradition. He was well-read in European literature and wished to secure Scotland’s place in the literary pantheon.

Then in 1603, Elizabeth I of England died, unmarried and childless. The son of her first cousin, once removed, Mary Queen of Scots, whom she had executed, now had the major claim to the English throne – and he was, like Elizabeth, a Protestant. James VI successfully negotiated to become Elizabeth’s successor as king of England as well as Scotland – James I of the United Kingdom. He and his court removed themselves from Edinburgh to London, and the nature of high Scottish literary language changed within a single generation.

Not all of the Scottish court went south – a few, like the poet, William Drummond of Hawthornden, who was educated at Edinburgh University and then in France, returned and stayed in Scotland. But even he turned to English as his preferred literary medium, and his library (which he carefully catalogued, and much of which is still housed at Edinburgh University) shows his interest in the works of Shakespeare and Jonson. This is part of his poem ‘Forth Feasting’ (1617), which regrets James VI’s preference for the river Isis (part of the Thames, which flows through London) over his native river Forth, which flows from Edinburgh to Stirling and beyond:

Ah why should Isis only see Thee shine?

Is not Thy FORTH, as well as Isis Thine?

Though Isis vaunt shee hath more Wealth in store,

Let it suffice Thy FORTH doth love Thee more:

Though Shee for Beautie may compare with Seine,

For Swannes and Sea-Nymphes with Imperiall Rhene,

Yet in the Title may bee claim’d in Thee,

Nor Shee, nor all the World, can match with mee.

The language of Drummond’s poem is inescapably Early Modern English, and the complaint is addressed to a king who spends much of his time abroad. The message is that Scotland is in danger of being marginalised, culturally and politically. How the nation’s writers dealt with this perceived marginalisation will take up much of the following chapters.

Further Reading and Links:

Bawcutt, P. (2001). James VI’s Castalian Band: A Modern Myth. The Scottish Historical Review, 80(210), 251-259.

Calin, W. (2013). The Lily and the Thistle: The French Tradition and the Older Literature of Scotland. University of Toronto Press.

van Heijnsbergen, T. (2009). Alexander Montgomerie. Poetry, Politics, and Cultural Change in Jacobean Scotland. Journal of Early Modern History, 13(1), 75-77.

Lyall, R. J. (1991). ” A New Maid Channoun”? Redefining the Canonical in Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature. Studies in Scottish Literature, 26(1), 3.

McClure, J. D. (1991). Translation and Transcreation in the Castalian Period. Studies in Scottish Literature, 26(1), 14.

An edition of James VI’s ‘Reulis and Cautelis’ can be found at https://archive.org/details/essaysofprentise00jameuoft

An online anthology of 16th century Scottish poetry can be found at: