In 1893, the painter Charles Martin Hardie completed a canvas portraying the only meeting between Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott, then a boy of around fifteen years of age. The meeting took place during the winter of 1786-7, at one of the literary dinners held by the philosopher, Adam Ferguson, at his home in Sciennes Hill House, Edinburgh, and the group portrait brings together some of the luminaries of what has become known as the ‘Scottish Enlightenment’. A powerful group of intellectuals across Europe were actively engaged in a mission to advance reason and science in place of superstition and supposition, and Edinburgh was widely acknowledged to be one of the centres of new ways of understanding history and contemporary society.

In Hardie’s portrait, besides Burns and Scott, we can see Adam Ferguson and his fellow philosophers, Adam Smith and Dugald Stewart; the physician, Joseph Black; the geologist, James Hutton; and the dramatist John Home, author of the immensely popular play, Douglas. A group of unnamed ladies congregates in a far corner, eyeing the poet curiously.

The painting is, of course, part fact, part myth. The encounter actually happened, and, according to some accounts, Scott came to Burns’ attention as the only person in the room able to identify the author of the lines inscribed on a print that visibly moved the older poet. Scott’s own later memory of the encounter, however, plays down his own prominence:

I was a lad of fifteen in 1786-7, when he [Burns] came first to Edinburgh, but had sense and feeling enough to be much interested in his poetry, and would have given the world to know him; but I had very little acquaintance with any literary people, and still less with the gentry of the west country, the two sets that he most frequented. Mr Thomas Grierson was at that time a clerk of my father’s. He knew Burns, and promised to ask him to his lodgings to dinner, but had no opportunity to keep his word, otherwise I might have seen more of this distinguished man. As it was, I saw him one day at the late venerable Professor Ferguson’s, where there were several gentlemen of literary reputation, among whom I remember the celebrated Mr Dugald Stewart. Of course we youngsters sate silent, looked and listened.

Even if Scott was not so clearly in the spotlight as Hardie suggests, the group portrait still represents a moment when the baton was passed from one extraordinary literary generation to the next. Scott was to inherit the legacy of Burns as a national poet, but he was also to professionalise the role of the literary author, reinvent the role of the novel as a means of interpreting history, and in doing so he transformed the way novels were written, published, and used by readers as a means of imagining the nation.

Scott, unlike Burns, was born into a professional family – he was the son of an Edinburgh lawyer whose family owned property in the Borders. It was the family farm in the Borders to which the infant Scott was sent when he contracted polio in 1772, the year following his birth. There, as he grew up, he became immersed, like Burns, in the oral traditions borne by storytellers and ballad singers. He also read the poems of Allan Ramsay, and so he encountered both Scottish oral culture and its printed counterpart from earlier in the 18th century.

In 1779, Scott was well enough to begin his formal education at Edinburgh High School, and despite occasional recurrences of his illness, he continued to Edinburgh University where he graduated in law in 1786. He began practising law while developing a parallel career as a ballad collector and anthologist, a cultural commentator and a poet in his own right. Between 1799 and 1814, he edited anthologies such as The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, and composed long narrative poems such as The Lay of the Last Minstrel, The Lady of the Lake and Marmion.

In their day, his poems were both critically acclaimed and astonishingly popular: to take one example, The Lady of the Lake (1810) sold 25,000 copies in six months. The poems stimulated a vogue for touring the sights associated with their narratives, in this case, Loch Katrine in the Trossachs, where, even today, visitors can take a boat trip on the S.S. Sir Walter Scott. The lasting – albeit indirect – impact of the poem in the USA can be heard every time the American President walks into a public gathering and the band strikes up ‘Hail to the Chief’, originally a musical setting, composed in 1812, to a boat song that appears in the second canto of Scott’s poem.

What made these poems so successful? Part of the attraction of Scott’s oeuvre seems to be his fusion of a personal narrative – usually anchored in a romantic dilemma – with aspects of Scottish history. The Lady of the Lake typifies the technique: against the real historical backdrop of a feud between James V and the Clan Douglas, Scott weaves the fabulous story of rivalry for the love of ‘Fair Ellen’, the eponymous ‘Lady of the Lake’, between ‘James Fitz-James’, Malcolm Graeme and Roderick Dhu. When Graeme is apparently sentenced to death, ‘Fitz-James’ hopes to win Ellen’s affections, but he soon sees his hopes dashed:

Fitz-James knew every wily train

A lady’s fickle heart to gain,But here he knew and felt them vain.

There shot no glance from Ellen’s eye,

To give her steadfast speech the lie;

In maiden confidence she stood,

Though mantled in her cheek the blood

And told her love with such a sigh

Of deep and hopeless agony,

As death had sealed her Malcolm’s doom

And she sat sorrowing on his tomb.

Hope vanished from Fitz-James’s eye,

But not with hope fled sympathy.

He proffered to attend her side,

As brother would a sister guide.

In the end, ‘Fitz-James’ is revealed to be the king, James V, in disguise, and it is his love for Ellen that reconciles him to her family, the Douglases. He graciously approves of her marriage to Graeme, a loyal highlander, who has escaped his death sentence; the other rival for Ellen’s love, Roderick Dhu, a highland outlaw, conveniently dies.

The poem, then, is not only a romance; it also functions as an allegory of past lowland-highland conflicts that are happily resolved in a united and harmonious kingdom: the benign lowland monarch’s platonic love for a highland woman reconciles the warring highland and lowland factions. Ellen’s preference for the loyal highlander, Malcolm Graeme, over the valiant but traitorous clan chief, Roderick Dhu, confirms the unifying sentiments of the poem.

Despite Scott’s commercial success as a poet, however, his financial affairs were to take a downturn in the three years after the publication of The Lady of the Lake. In 1810, Scott left the Edinburgh publisher Archibald Constable, and he published The Lady of the Lake with a new publisher, James Ballantyne, with whom he had quietly entered into partnership. The following year, Scott acquired a property in his beloved Borders, Cartley Hole Farm, where he began building a baronial mansion, which he called Abbotsford. By 1813, the cost of Abbotsford was soaring and Ballantyne’s was in financial difficulties. Scott needed to produce a best seller to offset the debts he owed himself, and which were owed by the publisher he now partly owned. Scott took a momentous decision: he decided to publish a novel.

In 1814, it was not entirely respectable for an established male poet to enter the predominantly female realm of fiction writing. It is true that there had been popular male novelists in the 18th century: Samuel Richardson was one of the English pioneers in the first half of the century, writing epistolary novels like Pamela (1740) and Clarissa (1747-8), which featured virtuous females resisting the sexual advances of predatory males. Richardson was later parodied by his successor, Henry Fielding, whose comic, picaresque novels featured male characters, like Joseph Andrews (1742) and Tom Jones (1749) travelling the country and having sexual misadventures.

The picaresque theme was adopted by the Scottish-born journalist, translator and novelist, Tobias Smollett, in novels like The Adventures of Roderick Random (1748), which often featured a Scotsman travelling to England, where his native wit ultimately ensured his rise above adverse circumstances. His later novel, The Expedition of Humphrey Clinker (1771) is another travelogue, notable for its portrayal of the different national types that made up Great Britain.

And yet there was still a sense that novels written by males were either comic or unsavoury. Amongst the major successes of the period were Gothic romances by Horace Walpole (The Castle of Otranto, 1764) and Matthew Lewis (The Monk, 1796). These tales of terror extended and deepened the sexual anxieties expressed by Richardson’s novels: again there was a common theme of endangered female virtue, to which was added the spice of exotic European locations and spiritually tortured, often Catholic, male predators.

The Gothic novel was parodied by one of the major English female authors of the period, Jane Austen, in Northanger Abbey (1803). Austen went on to establish a reputation as an acute observer of society in a series of novels that included Sense and Sensibility (1811) and Pride and Prejudice (1813), which balanced romantic female yearning with a sharply ironic sense of the vulnerable position of women in bourgeois English life. Meanwhile, in Ireland, the English-born novelist, Maria Edgeworth, was combining social satire, moral purpose and a historical perspective in novels like Castle Rackrent (1800) which cast a withering eye on four generations of Anglo-Irish landowners. The novel, then, in 1813, was widely considered to be rather a trivial form compared to poetry, associated with narratives of romantic love, Gothic melodrama and social comedy. This was not a territory to be encroached upon by a poet with an established reputation.

Thus it was that Waverley, or ’Tis 60 Years Since was published anonymously in 1814. Its authorship was an open secret, however, as Jane Austen’s letter to her sister, Anna, indicates:

Walter Scott has no business to write novels, especially good ones. – It is not fair. He has Fame and Profit enough as a Poet, and should not be taking the bread out of other people’s mouths. – I do not like him, and do not mean to like Waverley if I can help it – but fear I must.

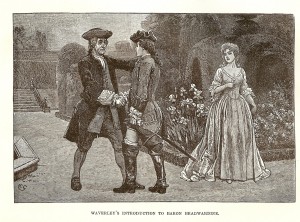

Waverley, in many ways, repeats in a novel the formulae of Scott’s successful poems: it draws upon Scottish history – here, the Jacobite rebellion that took place ‘60 years since’, in 1745 – to relate a personal story of a romantic dilemma. In this case, the allegory of Union moves beyond disunited highland and lowland Scotland to encompass all of Great Britain. The novel’s eponymous hero is an English soldier, Edward Waverley, who travels north to Scotland, where he comes under the spell of Jacobitism and, in particular, the Highland beauty, Flora McIvor, whose family supports the exiled Stuart dynasty. After a series of adventures, culminating in the Battle of Prestonpans, Edward is spurned by Flora, and he falls into the welcoming arms of Rose Bradwardine, a lowland Scot, from a family that supports the Hanoverians. As in The Lady of the Lake, then, Scott addresses the still-sensitive area of anti-Hanoverian sentiment, only to frame it as romantic, but doomed. The marriage plot that resolves the conflicts in the novel also serves to confirm loyal, lowland or Unionist values as opposed to highland subversion – although the latter is always viewed as both valiant and seductive.

Waverley initiated the respectable novelistic genre of the historical romance, and its phenomenal success changed the literary landscape, not least because publishers became less willing to take on poetry. The first edition of Scott’s anonymous novel sold out its 1000 copies in two days, and more novels ‘By the author of Waverley’ followed, all drawing on aspects of Scottish history to tell their stories: they include Rob Roy (1818), Heart of Midlothian (1818) and The Bride of Lammermoor (1819).

As well as Scottish history, Scott plundered English history for Ivanhoe (1819), French history for Quentin Durward (1823), and Middle Eastern history for The Talisman (1825). Despite his supposed anonymity, Scott was now a major cultural celebrity, and his standing was confirmed by his appointment to co-ordinate the visit of George IV to Edinburgh in 1822. This royal visit itself can be seen as enacting the rapprochement Scott sought between lowland and highland, Saxon and Gael, England and Scotland – the Hanoverian monarch dressed himself spectacularly in tartan, the hitherto outlawed costume of the Jacobite rebels. The event sparked a craze for tartanry that has lasted into modern times.

Even at the height of his literary success, however, Scott faced financial ruin. Three years after George IV’s visit to Edinburgh, in 1825, the financial markets collapsed, resulting in the bankruptcy of Ballantynes, and Scott found himself mired in debt. His response, as with the publication of his first novel, was to write himself out of debt and also to be commercially innovative, this time in marketing of the back catalogue of his work. In 1829, he launched the ‘Magnum Opus’ edition of his Waverley novels – a collectors’ edition with revised text, and new introductions and annotations. They were designed to be plush in their leather bindings, but affordable to a mass market. At the retail price of five shillings, they were published once a month between 1829 and 1833; as Scott scholar, David Hewitt, remarks:

Such was the interest in everything he did that they sold in huge numbers – 30,000 volumes a month. The profits were great and when Scott died in 1832 the debt had already been reduced by half.

When Burns passed on the baton of Scottish literature to the 15-year old he met in Sciennes Hill House, he could not have imagined the legacy that the young man would leave. Scott’s career saw the effective eclipse of poetry by fiction, the rise of the historical novel as a respectable form for male and female authors, the establishment of a mass market for affordable literary fiction and the invention of the best-selling author and the special edition of his works. Those works prompted a rise in cultural tourism that saw hotels built to cater to those visitors hungry to see the landscapes described in the novels, and even a fashion craze that changed the way Scots, lowland as well as highland, dressed for ceremonial occasions. More than anything, perhaps, Scott’s vision of Scotland allowed regional and national difference – in ethnicity, dress, behaviour, religion, dynastic allegiance and politics – to be acknowledged, admired and contained. The Jacobite past was made to appear exotic, seductive and noble, and, at the same time, it was doomed to be supplanted by the rational forces of Hanoverian, unionist progress.

As Kenneth McNeil has suggested, one short but representative illustration of Scott’s narrative achievement, that also serves as a useful introduction to his work, is the short story, ‘The Two Drovers’, published in 1827 in the collection Chronicles of the Canongate. This anthology of fictional episodes, set between 1750 and 1800, and linked by the narrator ‘Chrystal Croftangry’, was the first book that Scott openly acknowledged as his own.

Like Waverley, ‘The Two Drovers’ is structured as a journey between cultures, but instead of an English hero journeying to the Jacobite north, we find a highland drover, Robin Oig McCombich, journeying south to a cattle market in the north of England. On the way he meets his English friend and fellow drover, Harry Wakefield, and they travel in friendship until a series of misunderstandings at their destination leads to an inexorable spiral of violence that culminates in Robin’s premeditated murder of Harry. The story ends with Robin’s acceptance of a judge’s sentence of capital punishment.

McNeil observes that the story falls into three sections – a descriptive introduction, typical of Scott’s fiction more generally, that spends some time describing highland culture, customs, behaviour and beliefs. The intervention of a spaewife, or fortune-teller, prophesying disaster if Robin journeys south, adds a deterministic note to the oncoming collision of Scottish and English cultures.

The introduction is followed by the narrative of the journey to the cattle market – and the market, as Adam Smith had suggested in The Wealth of Nations (1776), seems to promise the possibility that people of different cultures can meet as equals, and, on the basis of professional solidarity and shared interests, put aside any ethnic, racial or cultural differences.

But fate intervenes – an apparently trivial misunderstanding causes Harry to lose face, and he responds by knocking Robin down in public, in an unequal wrestling bout. This act, in turn, causes Robin to lose face, and his only response is to return later with a knife. The ethnographic introduction to the story invites a cultural interpretation of the main narrative, and this is what the judge provides, if somewhat stereotypically, in the summing up that concludes the story. The English judge allows that Robin comes from a culture that allows no option but to respond to a perceived insult with deadly force – and while acknowledging the valiant ethos that gives rise to such values, the judge states that they have no place in a civilised society, and so he sentences Robin to death. Robin’s role, of course, is to acquiesce, and the reader’s role is to follow the judge in admiring Robin’s courage and understanding his motives, even while condemning his violence as the backward response of an uncivilised savage.

‘The Two Drovers’ is in some ways a bleakly pessimistic tale: it celebrates the colourful nature of different communities while affirming that tragedy is inevitable when these communities come into contact. And although the market might be a cultural melting pot where communities can meet on an equal footing, any friendship based on mutual professional interests only lasts so long. Conflict is ultimately unavoidable, and when it occurs, the values of the dominant culture, here the ‘civilised’ English culture, must prevail – a conclusion that Scott invites his readers to consider and endorse.

It is of course possible to read ‘The Two Drovers’ against the grain, and to resist the dominant interpretations of Walter Scott’s fiction. We need not endorse Robin’s sentence at the end of the story – and we can point to the ways in which the interactions between the dominant and marginalised cultures constrain his fate so that Robin, as much as Harry, is seen as the victim of a murderous culture. Like all fabulists, Scott can be read in different ways.

At the very least, we can argue that, beginning with Waverley, Scott opened up the novel, and fiction more generally, as a space to explore the interactions between the historical, the cultural and the personal. He sparked a popular and abiding interest in Scotland’s history, landscape and people, and cemented the image of the Scots as a people who must accept progress, which is attractive, inevitable but dull, or else resign themselves to heroic, passionate, romantic, but equally inevitable oblivion.

The cultural dilemma facing the Scots – the choice of progress or romantic oblivion – touched an international nerve. Over the next century and a half, the popularity of Scott’s fiction saw it transformed into plays, operas, comic books and Hollywood films. Scott also opened up a space for other Scottish novelists, and into this space poured a succession of writers whose engagement with Scottish history and the Scottish psyche were indelibly to mark the rest of the 19th century.

Further reading and links

David Hewitt was quoted in an article in the Daily Record on 27 December 2012: ‘Revealed: How Sir Walter Scott’s literary jewels were saved by the Daily Record and Sunday Mail’

McNeil, Kenneth (2009). ‘The Limits of Diversity: Using Scott’s “The Two Drovers” to Teach Multiculturalism in a Survey or Nonmajors Course’, in Approaches to Teaching Scott’s Waverley Novels, ed. Evan Gottlieb and Ian Duncan (New York: Modern Language Association of America), pp. 123-29.

Robertson, Fiona (2012). The Edinburgh Companion to Sir Walter Scott. (Edinburgh: EUP)

The Walter Scott Digital Archive at Edinburgh University Library is full of information and resources for the study of Scott and his work.